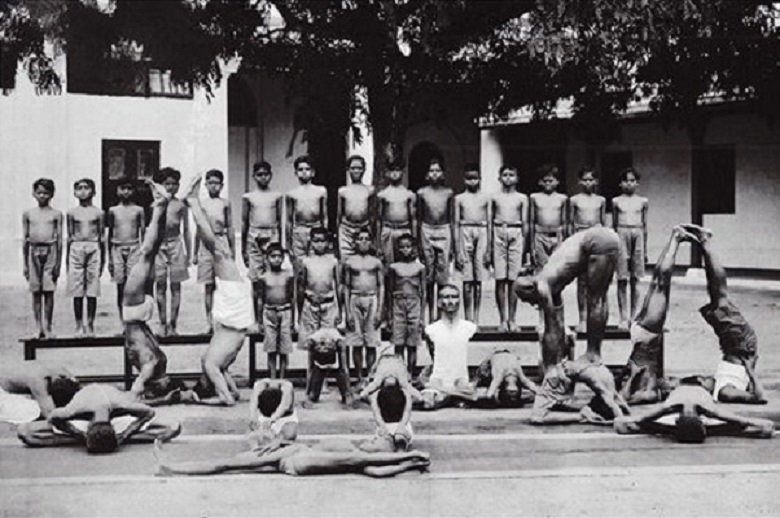

Warlike Indian monks bathe during the Kumbha Mela religious festival.

|

You are on the page: Scriptures.ru ➤ Meditation book ➤ Hatha yoga real origin

|

Where did the nowaday yoga come from, or a brief real history of hatha yoga

This article provides a versatile overview of the history of yoga from the times of writing the well-known ancient scriptures of India to the present day.

In the most ancient texts of Hinduism – the Vedas – yoga as such is not mentioned, although these texts themselves were written by the holy sages, who described, among other things, their sublime states after achieving the yoga realization.

The first chronologically and most significant yoga text with indisputable authority is the Yoga Sutras of the holy sage Patanjali, dating from the 2nd century BC until the 4th century AD. Originally written in Sanskrit, from the moment of its appearance to the present day, the Yoga Sutras remain the fundamental scripture of all yoga, its "bible". The first two stanzas of this text immediately talk about what yoga is.

अथयोगानुशासनम्॥१॥

atha yoga-anuśāsanam ॥1॥

1. So, instruction in yoga.

योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः॥२॥

yogaś-citta-vr̥tti-nirodhaḥ ॥2॥

2. Yoga is the taming of the agitations of the mind.

In other words, yoga is the process of gaining control over the mind. This is the activity of consciousness.

From the 3rd century BC until the 8th century AD Buddhism dominated in India. It arose as a result of the Buddha borrowing from Hindu yoga the practical methods of achieving self-realization – moral precepts and meditation. Later, the practices of Buddhism began to develop independently, but to a large extent they remained a cast of the best that was in the yoga of that time. Tellingly, in Buddhism (as well as in the "Yoga Sutras" of Patanjali) there is practically the only posture (asana) for meditation – sitting with a straight back. The observed variations of this pose differ mainly in the position of the hands.

The Sanskrit word “asanam” (āsanam) is derived from the root “ās” – “to sit” (āsa) – by adding the suffix –ana, giving the action to the original meaning. That is, an asana is a "sitting" or sitting position. In this sense, the phrase "standing asana" is an oxymoron that arose after numerous modifications of the original meaning of the word. The same applies to other asanas in which the yogi does not accept a sitting position. Here you can recall the naturalist Cratilus, who argued in a dispute with the conventionalist Hermogenes that words reflect a "natural similarity" between the form of the word and the thing depicted by it. In addition, the Yoga Sutras have a clear definition of asana:

sthira-sukham āsanam ॥46॥

46. Asana is that which has [properties] of stability and pleasantness.

As we can see, even in this definition itself there are no moments of the training approach and loads on the body. It is unlikely that you will be able to improve muscle tone or stretching while staying in a comfortable and pleasant position. In addition, Patanjali does not indicate a variant of the position of the body, since the origin of the lexeme "asana" clearly indicates that this is a sitting posture, and the author of the Yoga Sutras did not consider the rest of the details to be important enough to describe them. If we start from logic, then, from his point of view, they are not really significant. One well-known distinguishing feature of sitting postures in which you can be comfortably for a long time is a straight back.

In the XII-XIII centuries Arabs, Turks and Afghans invaded North India, and significant changes began to take place in the religious life of Hindustan again. The influence of Islam on Indians and Hindu religious movements, among other things, has led to the emergence of new religious movements, such as Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Bengal with its monotheism that is uncharacteristic for Hinduism, and which is at the same time inherent in Islam.

In Indian traditions, sannyasa (monasticism) has historically been a stage of renunciation, ahimsa (non-violence) peaceful and simple life and spiritual pursuit. However, this has not always been the case. After the invasions and establishment of Muslim rule in India, from the 12th century through the British Raj (the rule), parts of the Shaiva (Gossain) and Vaishnava (Bairagi) ascetics continued the reorganization (begun by Shankaracharya in the 9th century) into the military orders, where they developed martial arts, created military strategies, and engaged in guerrilla warfare. These warriors-sannyasis (ascetics) played an important role in helping European colonial powers establish themselves in the Indian subcontinent, acting as the then PMCs (private military companies), hiding behind the signs of quasi-monastic "one-day" organizations, and masking physical training with "spiritual" new-made ascetic practices. Looking ahead, it can be noted that in the 19th century, when the need for these paramilitary organizations for the British disappeared, and they began to create problems for the East India Company itself, as a result of various actions by the British administration, these paramilitary organizations actually ceased to exist.

In this context, it is quite appropriate to quote the description of the book by William R. Pinch “Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires”:

“Many people assume, largely because of Gandhi's legacy, that Hinduism is a religion of non-violence. In this 2006 book William R. Pinch shows just how wrong this assumption is. Using the life of Anupgiri Gosain, a Hindu ascetic who lived at the end of the eighteenth century, he demonstrates that Hindu warrior ascetics were an important component of the South Asian military labor market in the medieval and early modern Indian past, and crucial to the rise of British imperialism. Today, they occupy a prominent place in modern Indian imaginations, ironically as romantic defenders of a Hindu India against foreign invasion, even though they are almost totally absent from Indian history. William R. Pinch's innovative and gloriously composed book sets out to piece together the story of the rise and demise of warrior asceticism in India from the 1500s to the present. It will appeal to students of religion and historians of empire”.

Around the same time, it is believed that a new direction in yoga appeared – hatha yoga. It is focused primarily (if not entirely) on working with the physical body, and a variety of poses appears in it, among which power asanas appear for the first time, completely unsuitable for prolonged meditation and directly contradicting the above stanza 2.46 from the Yoga Sutras. Regular performance of these power asanas can have a certain therapeutic effect, and, like calisthenics, it helps to increase muscle tone without using any weights and simulators (only the weight of the body itself is used as a load), which was in demand in the era of continuous medieval wars in Indian subcontinent, when the cult of physical strength and agility flourished in society.

The main texts of hatha yoga appeared in the 15th-17th centuries during the Hindu Renaissance at the time of the Vijayanagar Empire, which practically all the time of its existence resisted the armed invasion of Muslims from the north of India that they had already captured. Now it is no longer possible to reliably find out whether the texts of hatha yoga that appeared at that time were the result of governmental grants or written by demand of the leadership of the Akhara organizations (monastic orders, in each of which, as early as the 9th century, Adi Shankaracharya divided monks into shastradhari, or "scripture-bearers" intelligentsia, and astradhari – "weapon-bearers" armed fighting groups among "monks", usually making up the majority of participants in any akhara; it was these militant groups that, among other things, took by storm the Buddhist monasteries in Sringeri, Badrinath, etc., in the place of which Shankaracharya founded his Hindu Math organizations and temples) to popularize physical culture, but we can definitely say that they very successfully and very timely connected local cultural and religious traditions (yoga) with the promotion of physical training in the form of calisthenics. As one of the historical examples of the promotion of the cult of physical strength and dexterity at the state level, one can cite the Soviet propaganda of the “Ready for Labour and Defence” (“GTO”, “Gotov k trudu i oborone”) program (1931-1991, partially has begun to be revived since 2003 in the Russian Federation, officially introduced again on 03/24/2014, coverage of the population aged from 10 to 60 years old; the German counterpart “Sportabzeichen” was introduced in 1913, a year before the First World War, and PE – physical education – program was obligatory for youth in Nazi Germany) for physical training, in this case, "Pskov" Russian youth for the military scenario of "world revolution". Whenever the government is forced to fight for a long time with the armed aggression of the "neighbor" (as in the case of the Vijayanagar Empire), or the totalitarian regime prepares for aggression (as in the case of the Kremlin), state propaganda of physical training is almost inevitable, especially in the Middle Ages or in countries whose leadership is stuck in the Middle Ages in terms of its mental level of development.

The classic text, as well as the first chronologically, in which many practices of hatha yoga are systematized, was the work of Swami Svatmarama "Hatha yoga pradipika" (most often dates back to the 15th century). In this text, the term "raja yoga" appears for the first time as a retronym (a new name or name changed after the original name was used for another object or for a combination of a new object and a pre-existing one), introduced into use to establish a distinction of the school based on "Yoga Sutras" from a new trend – hatha yoga. It should be noted that there is no mention of hatha yoga in Patanjali's Yoga Sutras. Swami Svatmarama belonged to the Saiva yoga tradition from Andhra.

Modern researchers associate the emergence of hatha yoga with Matsyendranath and his disciple Gorakshanath, mentioned in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika itself, who is believed to have founded the hatha yoga tradition of the nathas in the X-XI centuries. Based on separate later references in different texts, researchers believe that Gorakshanath systematized the practices of working with the body and mind existing in his time, and also supplemented them with tantric elements. He is considered to be the author of many texts on hatha yoga (Goraksha paddhati, Goraksha shataka, Jnana amrita, Aman yoga, Yoga martanda, Siddha siddhanta paddhati, etc.). At the same time, for thousands of years in India, the practice of attributing their texts to legendary personalities by little-known authors in order to impart authority and popularity to the texts was widespread, and such works were not always in their own way as brilliant as, for example, similar musical creativity (attributing their works to famous authors of the past for one reason or another) of Vladimir Vavilov in the XX century. Most of the additions and alterations of the "classical" texts of Hinduism (Puranas, Upanishads and others) happened during the Vijayanagar Empire (XIV-XVII centuries).

Hatha yoga further developed in the 17th-18th centuries, which coincided with the emergence of the British East India Company in India (in 1617, the British East India Company received the right to trade with India from the Mughal Emperor Jahangir) with its colonial army and army drill. The following texts are attributed to this time: "Gheranda samhita", written by the Vaishnava sage Gheranda from Bengal; "Yoga Karnika" by Aghorananda; "Hatha sanketa chandrika", attributed to Sundaradeva, and others. Also, Georg Feuerstein attributes to the 18th century the "Shiva-samhita". In this text, along with practices, the philosophy of hatha yoga is set forth.

The emergence of a number of new postural yoga texts was accompanied by one interesting feature. In some of the most famous hatha yoga texts, like Goraksha Paddhati and Gheranda Samhita, there is no mention of yama and niyama, the moral precepts of yogis that include nonviolence (ahimsa). Unlike Patanjali's eight-part Yoga Sutras, in Goraksha Paddhati there are only 6 parts (sometimes called steps), and in Gheranda Samhita there are seven, which is achieved by removing the yama and replacing niyama with shatkarmas (physical cleansing procedures). Perhaps someone will argue that morality, including nonviolence, is already implied for someone who claims to be a monk, moving on the path to spirituality. But to this we can say that, firstly, many of the no less obvious and much less significant things are nevertheless described in detail in these texts. Secondly, the actual combat orientation of the "monastic" orders-akharas, including those related to the natha sampradaya (to which both these texts are referred), was so conspicuous in the Middle Ages that it came into simply inconceivable and anecdotic contradiction with the fundamental concepts of yama and niyama of the then yoga, based on the "Yoga Sutras" of Patanjali. This contradiction was at least partially resolved only by writing new special texts, from which the requirement for observance of ahimsa by "yogis" – the name the militant supporters of physical training & calisthenics called themselves – had to be thrown out. Against this background, it is interesting that in the Indian edition of the English translation of Shiva samhita in 1914 in stanza 3.33 "Things to be abandoned" in paragraph 11 the word "himsa" (violence) is translated as "killing (animals)" with the addition of the word "animals" in brackets, which is absent in the Sanskrit original, although paragraph 19 of the translation separately speaks of "cruelty towards animals (prANi-pIDA, "pain to alive")", although even there in the Sanskrit original we are talking about simply living beings – prANin, including humans. Apparently, the idea of the violent sannyasins was so ingrained in the minds of Indians that they could no longer, in translating even such a text as Shiva samhita, not shift the emphasis on the need to manifest non-violence only in relation to animals, since the violent attacks of armed sannyasins were then perceived by the Indians as something for granted.

Below are selected quotes from Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami's "Dancing With Siva: Hinduism's Contemporary Catechism":

Warlike Indian monks bathe during the Kumbha Mela religious festival. |

Interestingly, in Hinduism, the dominant point of view is that hatha yoga arose from tantra among the nathas. But at the same time, for some reason, hatha carries in its name the lexeme "yoga" and not "tantra", although a name like "hatha-tantra" would be quite logical. Or, the name hatha-vyayama – hatha gymnastics, would be more reliable if we take into account the virtually complete dominance of gymnastic exercises over shatkarmas and especially dhyana (meditation) in the actual practice of hatha (including in the now popular ashtanga vinyasa). But, of course, if the hatha system was created as a cover for calisthenics, then it was necessary to veil physical training, "anchoring" the name of the new system – hatha yoga – on the classical religious tradition (yoga), thereby masking physical training. But, what is even more interesting, allegedly appearing among the nathas, hatha yoga was completely forgotten by them practically in the same 15th century (in which it became at least in some way known), which cannot but lead to speculation about whether did they really have it at all. It is possible that these wandering sadhus, who have always ignored society and in their overwhelming majority could not read, could simply be attributed to hatha, and even retroactively.

Excerpt from the article “Interview with Christopher Wallis. Tantric roots of hatha yoga":

“Question: It is interesting that among the Indian yoga teachers who spread hatha yoga in the West, no one belongs to the natha sampradaya (in the Middle Ages, the guardians of hatha yoga). Krishnamacharya was from the Sri Vaisnava sampradaya, Sivananda and Satyananda belonged to the Sarasvati order (advaita vedanta), etc. Several years ago I was looking for such people in India, but it looks like nathas no longer practice hatha yoga at all.

Answer: No, they don't practice. It is very important that you know about this, because in fact, nathas have not practiced hatha yoga for four hundred years. Do you know James Mallinson? He is a very important scholar who studies hatha yoga, because he not only reads Sanskrit well, but also lived for many years in India with yogis, sadhus, naga baba, that is, he is familiar with the real facts and reads ancient texts. He says that for some reason the nathas stopped practicing real yoga, and people call them yogis (actually “jogis”), simply because this is the name of the caste, and they do not practice hatha yoga".

Studying the history of yoga, jogis, tantra, nathas and the Vijayanagar empire allows person to get a certain idea of the environment, in what context and for what purposes hatha yoga appeared. In world history, it was not the only cultural or religious phenomenon (along with Brazilian capoeira and even the creation of Wahhabism by Lawrence of Arabia), which was used as a cover for pragmatic and completely mundane goals. In this case, for the military strength training-callisthenics of the monastic orders-akharas, who acted as the then PMCs or, during periods without wars, often lived according to the principle of the Makhnovshchina (One example: the sannyasin uprising of 1770-1820; historians have not only debated what events constitute the rebellion, but have also varied on the significance of the rebellion in Indian history. While some refer to it as an early war for India's independence from foreign rule, since the right to collect tax had been given to the British East India Company after the Battle of Buxar in 1764, others categorize it as acts of violent banditry following the depopulation of the province in the Bengal famine of 1770. Among the Hindus sannyasis the akhara of Dashanami sampradaya were major participants.).

The book by Mark Singleton "Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice" provides the most detailed and reliable history of both the emergence and formation of hatha yoga over the past centuries, and the change in the perception of the image of a hatha yogi over the past 150 years from the despised by Indian society marginalized homeless who was engaged in scams with fortune-telling, theft, robbery and utterly disgusting rituals of black magic, to the modern glamorous (hatha) yoga practitioners of the current not devoid of traumas yogabiz. This book explains in detail that hatha yoga was created, among other things, as a cover for fitness for the warlike "akhara" orders of "monks" who have robbed trade routes at least since the days of the East India Company. Quoting from Chapter 5: “We might also note in passing that this secret honing of martial skill under the guise of yoga-asana bears comparison with the development of nineteenth-century Brazilian capoeira as an indigeous combat technique disguised as dance. This reconstruction of the spirit and practice of the violent sannyasin led to a continued association of hatha yoga with the culture of martial exercise exemplified by the militant ascetic".

Some of the therapeutic effect of various means of hatha yoga could be in demand in the Middle Ages, when there was no modern medicine with its most diverse advanced means of diagnosing and treating diseases. But even in this matter, hatha yoga is a "remake" (new invention), significantly inferior to the ancient Indian medicine already available at that time – ayurveda.

As early as the 19th century, new techniques were added to the array of hatha yoga practices, in part influenced by British military training. In particular, standing techniques, and basically these are quite late additions (see above the etymology of the word "asana"). One of the first to promote new methods of hatha yoga was Raghavendra Swami (1890-1996), also known as Tiruka ("beggar"), who traveled around India posing as a yoga teacher and teaching people about it (actually teaching fitness; as he said he taught the exercises to 4.5 million people) as a way to fight the British colonists. At the same time, the main place of teaching hatha yoga for Raghavendra Swami was the village of Malladihalli in the same district of Chitradurga, in which Krishnamacharya was born in 1888, which will be described in detail below. Also in world history there is at least one more case (Briton Lawrence of Arabia) of the actual creation of a new religious teaching to cover a military special operation.

Subsequently, the efforts of teachers of (hatha) yoga to eliminate the practice of real meditation (Buddhist shamatha and yogic samadhi, replaced by guided meditation, which contradicts the essence of meditation – the active role of the will of the meditator himself) and, in fact, a complete shift in emphasis on physical education and physical action led to the fact that now yoga is usually understood as hatha yoga. Now the first impression for most people when they hear word yoga is not the curbing the agitations of the mind in meditation, but the difficult-to-achieve asanas, in which there is usually no possible to keep serenity and silence of the mind. Hatha yoga has already turned into yogabiz (by analogy with showbiz) and has practically changed the original meaning of the yoga word. Mass consumers do not need citta-vr̥tti-nirodhaḥ (curbing the agitations of the mind), they need postural "general strengthening gymnastics" given in physical sensations, in which visible progress is possible (for example, the development of joint flexibility and at least moderate muscle tone). And if all this is also served with the sauce of spirituality... Demand creates supply.

The excerpts from the Wikipedia article on hatha yoga: “The Sanskrit word हठ haṭha literally means "force" and thus alludes to a system of physical techniques... In the 20th century, a development of hatha yoga, focusing particularly on asanas (the physical postures), became popular throughout the world as a form of physical exercise. This modern form of yoga is now widely known simply as "yoga".” The following is the history of hatha yoga over the past one and a half hundred years.

The forefather of almost all modern hatha yoga is Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888-1989). Its actual role in spreading it around the world is enormous. For a complete understanding of how yoga appeared and what it became in the West, below is the history of Krishnamacharya, as well as his three main students – Pattabhi Jois (fellow villager), B. K. S. Iyengar (brother-in-law) and T. K. V. Desikachar (son). The history of Krishnamacharya is long, because this personality was extraordinary, and his influence on the nowaday hatha yoga is fundamental.

Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya

Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya was born in what is now a state of Karnataka in Chitradurga District to a family of orthodox brahmins of Tamil origin. He was the eldest of 6 children, including 2 brothers and 3 sisters. When he was 10 years old, his father died and the family moved to Mysore.

Since childhood, Krishnamacharya received a diversified education in various schools and colleges (in fact, he switched from course to course with breaks in different educational institutions, and did not receive a single diploma upon graduation; many years later he received at least one diploma), attended the universities of Benares (Varanasi), Mysore and Patna, and also did a lot of self-education. According to him, he became an expert on six darshanas (Indian philosophical schools, their names: Vaisesika, Nyaya, Sankhya, Yoga, Mimamsa and Vedanta), logic, Sanskrit, learned to play veena – one of the most ancient stringed instruments in India. It should be noted that all this is known only from the words of Krishnamacharya himself – from the stories that he later told in different versions to his disciples.

In the life of Krishnamacharya, as he later said himself, various mystical events took place. At the age of 16, Krishnamacharya allegedly had a strange dream in which his ancestor, the legendary yogi and Vaishnava saint Nathamuni, who lived 12 centuries earlier, sent him to the city of Alwarthirunagari in the neighboring state of Tamil Nadu. Krishnamacharya obeyed the dream and went there. As Krishnamacharya later said, when he arrived at his destination, he fell into a trance and found himself in the presence of three sages. He asked the sages to give him instructions from the Yoga Rahasya (The Mysteries of Yoga, this is not the Yoga Rahasya of Dattatreya; the son of Krishnamacharya, T. K. V. Desikachar openly stated that he saw how Krishnamacharya himself composed the stanzas of this text and edited them, adjusting them to the desired poetic size of Sanskrit, and also invented regular asanas and at the same time attributed them to "his teacher"), a long-lost yogic tradition of Nathamuni. One of the sages, whom he later identified as Nathamuni himself, began to read the text. When Krishnamacharya later came out of his trance, he was able to remember all the verses of this legendary treatise. In this way this story was subsequently presented by Krishnamacharya himself, who wrote this book possibly in 1937 (33 years after the "meeting" with Nathamuni), and first mentioned it and quoted it in 1954. It was first published in 1998, 9 years after his departure. The book contains 277 stanzas, grouped into 4 chapters. The same number of chapters in the Yoga Sutras (196 stanzas) and Hatha Yoga Pradipika (382 stanzas).

During his studies, Krishnamacharya continued to practice yoga as taught by his father as a child. Krishnamacharya also studied with yoga master Sri Babu Bhagavan Das. Many of Krishnamacharya's instructors, as he himself later recounted, recognized his outstanding ability in the study and practice of yoga and supported his progress. Some asked him to teach their children.

According to Krishnamacharya, during his vacations, which lasted about three months, he made pilgrimages to the Himalayas. At the suggestion of Ganganath Jha, Krishnamacharya sought to find a master named Yogeshwara Ramamohana Brahmachari, who was rumored to have lived in the mountains outside Nepal. For this, Krishnamacharya allegedly had to obtain permission from the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, Lord Irwin in the city of Shimla, who at that time was suffering from diabetes. As Krishnamacharya later said, at the request of the Viceroy, he went to Shimla and taught him yogic practices for six months. The viceroy's health improved, and he was imbued with respect and affection for Krishnamacharya. In 1919, the Viceroy allegedly secured Krishnamacharya's trip to Tibet, escorting him with three assistants and taking care of the expenses. It should be noted that this very controversial and arithmetically inconsistent story is known only from the words of Krishnamacharya himself, and he first told about these events only decades later.

After two and a half months of travel, Krishnamacharya allegedly arrived at Sri Brahmachari's school in a remote cave at the foot of Mount Kailash, where the master lived with his wife and three children. Under the tutelage of Sri Brahmachari, Krishnamacharya allegedly spent seven and a half years studying the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, asana and pranayama, and learned the therapeutic aspects of yoga. He allegedly memorized the unknown text "Yoga Kurunta" in the Himalayan Gurkha language. Traditionally, at the end of his studies, Krishnamacharya asked the guru what his teacher's salary would be. The master replied that Krishnamacharya should "get married, raise children and be a yoga teacher." It should be noted that there is no documentary or any other evidence of these stories. Moreover, under other circumstances, Krishnamacharya claimed that he found the manuscript of the Yoga Kurunta on palm leaves in the library of Calcutta, and that this manuscript, he claimed, was subsequently eaten by termites. Not a single copy of it (apart from the text of Krishnamacharya) has been found so far.

All this very controversial and arithmetically inconsistent story was written down from the words of Krishnamacharya himself by one of his closest students – A. G. Mohan, who personally studied with him in 1971-1989. Based on his own recollections of what he heard, the diaries of Krishnamacharya and recorded materials, A. G. Mohan wrote the book "Krishnamacharya: His Life and Teachings" and published it in 2010. Not only the alleged 8 "Tibetan" years of Krishnamacharya's absence in India do not fit in this story (already 6 years after the start of an 8-year trip to Tibet – in 1925 – he, allegedly after "returning from Tibet", married in India), but also the fact that Lord Irwin arrived in India for the first time only in 1926, assuming the duties of Viceroy and Governor-General of India (until 1931), and this appointment of Lord Irwin took place only 7 years after the version of events invented by Krishnamacharya, according to which Lord Irwin in 1919 allegedly already lived in India while in office (which is not true).

If this whole story were true, then it is absolutely impossible to believe that Krishnamacharya was invited to the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, taught him yoga for six months, lived at that time somewhere in his residence, treated him for diabetes (in fact, Lord Irwin was thin, and there is no mention in his biography that he suffered from diabetes; 85% of diabetics are obese), received from him a comprehensive help to travel to Tibet, and later merely confused the name of this Viceroy. It is also completely impossible to believe that Krishnamacharya confused the years allegedly spent next to his Tibetan guru, all the more so strongly. And it is impossible to believe that A. G. Mohan, who adores Krishnamacharya and was his favourite disciple, confused something in the diaries, recorded materials and personally heard conversations of his teacher. The only logical explanation in this chain of events is that Krishnamacharya simply fabricated the story of visiting Tibet from start to finish.

It is also worth noting the statement of Krishnamacharya that he allegedly needed the permission of the whole Viceroy of India in order to visit Tibet. The fact is that before the appearance of the PRC in 1949, there was no check of the Indians when crossing the border between India and Tibet in the Kailash region, located 100 km from the border with India (approximately in the area of the city of Pithoragarh, the route in those days was passable in summer for pilgrims), and one very old Indian guru said that he acquired a passport for the pilgrimage to Kailash only in the 1950s because of the Chinese checkpoints on the border with India. Prior to that, there were no visas or borders for Hindus visiting Tibetan Kailash. The whole story was clearly fabricated by Krishnamacharya to give himself importance.

“After Tibet” Krishnamacharya returned to Varanasi. As Krishnamacharya told later, Maharaja of Jaipur offered him the head of the vidyashala (Vedic school) in Jaipur; but since he did not want to be accountable to many people, Krishnamacharya soon returned to Varanasi. “In accordance with the wishes of his guru to live the life of a householder”, Krishnamacharya married Namagiriamma in 1925. After his marriage, circumstances forced him to work on a coffee plantation in Kaushika village in Hassan district in Karnataka state. It should be noted that 7 and a half years of allegedly living at the foot of the Tibetan Kailash do not arithmetically fit into the biography of Krishnamacharya even in the version that he told himself, since together with 2.5 months of travel from Shimla and no less time back to India it turns out 8 years, but at the same time Krishnamacharya married in India in 1925, although he had to get to India “after Kailash” no earlier than 1927, and then find a future wife and organize a wedding, and all this also takes time. In addition, the very fact of his only marriage at the age of 37 raises doubts about his actual date of birth, since usually in India the age of marriage at that time rarely exceeded 20-25 years. Most marriages at that time were between the ages of 14-18 or even earlier.

Here you can read the first chapter from the book by A. G. Mohan "Krishnamacharya: his life and teachings." In this book, the author writes that under different circumstances at different times, Krishnamacharya cited different contradictory versions of his biographies.

In a brochure that Krishnamacharya published in the 1960s, he writes that he allegedly lived in Tibet in 1911-1918, and not in 1919-1926(7), although he mentions all the same Lord Irwin, who was actually in India from 1926 to 1931, and, according to one of the versions of Krishnamacharya, during 7.5 years of studying with his Tibetan guru in a cave at Kailash, he allegedly traveled every year from there to the Indian city of Shimla, where he lived for 3 months every year to treat Lord Irwin's diabetes and teach him yoga, and then traveled back to Kailash every year. It should be noted that Lord Irwin lived in India for 5 years, not 7, and not in the years that Krishnamacharya spoke about; after being appointed to their office, the viceroys of India did not stay in this country for more than 5.5 years, usually it was exactly 5 years (and not at least 7 according to Krishnamacharya's version).

In one of the versions of his biography, Krishnamacharya mentions that he visited Varanasi twice, returning to Mysore between visits. In another version of his biography, Krishnamacharya mentions that he visited Varanasi only once, having lived in it for more than 10 years. Wikipedia until now (2020) says that Krishnamacharya in 1906 at the age of 18 years entered the Hindu University in Benares, but this educational institution will appear only in 1916.

The information that A. G. Mohan very selectively cites in his book is taken, firstly, from recorded personal conversations with Krishnamacharya, secondly, from a short autobiography written by Krishnamacharya, and thirdly, from his biography, which appeared in the Tamil magazine Kalaimagal, which is based on an interview with Krishnamacharya in 1984.

A. G. Mohan himself complains that there is no information about the early years of Krishnamacharya's life, besides his own words – no one else (besides Krishnamacharya) is able to confirm the fact of traveling to Tibet to the guru, just like no one can confirm the fact of his studies in various Indian universities, in which Krishnamacharya, according to him, allegedly received diplomas (there is no his name in the archives of universities).

A more or less reliable part of Krishnamacharya's biography begins only with his marriage to Namagiriamma in 1925 and subsequent work on a coffee plantation in the village of Kaushika in the Hassan district of Karnataka state. It is also known that Krishnamacharya opened a small school of (postural) yoga in Mysore on August 11, 1933. At this time, the first documentary evidence appears – archival records of the palace, which show that the Maharaja was interested in promoting yoga and often sent Krishnamacharya around the country to give lectures and conducting demonstrations (yoga asana complexes). The following is again the version of his biography that Krishnamacharya recounted decades later in various conversations.

In 1926, the Maharaja of Mysore – Krishna Raja Wodeyar IV (1884-1940) – was in Varanasi to celebrate his mother's 60th birthday and heard about Krishnamacharya's qualifications as a yoga therapist. Maharaj met with Krishnamacharya and was so impressed by the young man's behavior, charisma and knowledge that he invited Krishnamacharya to teach him and his family. Originally, Krishnamacharya was supposed to teach yoga at the Mysore Palace. He soon became a trusted advisor to the Maharaja and was recognized by the palace intelligentsia.

In the 1920s, Krishnamacharya held many demonstrations to stimulate the popularity and interest in yoga. These include pausing his pulse, stopping the car with his bare hands, performing difficult asanas, and lifting heavy objects with his teeth. The archival records of the palace show that the Maharaja was interested in promoting yoga and constantly sent Krishnamacharya around the country to lecture and hold demonstrations.

Demonstration of asanas in the Mysore palace by Krishnamacharya. Krishnamacharya on the right side of the picture stands on a boy. Pattabhi Jois claimed that in the picture he is the same boy that Krishnamacharya stands on (in fact, Krishnamacharya stands on a boy named T. R. S. Sharma). But the inquisitive minds of caring activists are inclined to believe that in reality Pattabhi Jois is the dark-skinned hatha yogi on the far left standing on his head. |

In 1931, Krishnamacharya was invited to teach at the Sanskrit College in Mysore. Maharaja believed that yoga helped cure him of many ailments, and therefore asked Krishnamacharya to open a yoga school under his auspices. Subsequently, a wing at the nearby Jaganmohan Palace was set aside for the school to establish an independent yoga school. The school opened on August 11, 1933.

In 1934, Krishnamacharya published a book called Yoga Makaranda, which was published at the University of Mysore. In the introduction, Krishnamacharya mentions Sritattvanidhi, a 19th century treatise by maharaja of Mysore Krishnaraja Wodeyar III (1794-1868), as one of the sources for his book. This treatise contains a section on yoga with descriptions and illustrations of 122 asanas, which in fact makes it the most significant text on asanas published before the 20th century.

Norman Sjoman, a Canadian of Swedish origin, studied Sanskrit scriptures in India for 14 years and practiced yoga from 1970 to 1976 in B. K. S. Iyengar, in his book "Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace" (1996), claims that Krishnamacharya was influenced by the treatise "Sritattvanidhi", as well as "Vyayama Dipika" – a book based on the West gymnastics manuals, written by the gymnasts of the Mysore Palace.

In the mid 1980s, while doing research at the Mysore palace, Sjoman made copies of the yoga section of the Sritattvanidhi, a "colossal" illustrated compendium, authored in the 19th century in Karnataka by the then maharaja. The book included diagrams of 122 yoga asanas. Unlike the few other known historical yoga treatises, the emphasis was solely on the physical activity. Some appeared based on Indian wrestling and other gymnastic exercises, in that aspect more closely resembling modern yoga as exercise forms such as Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga of Pattabhi Jois.

Palace of the Maharaja of Mysore "Amba Vilas" |

The book Sritattvanidhi is notable for its innovative combination of hatha yoga asanas with rope exercises used by Indian wrestlers and strength exercises (such as Indian push-ups, or dand push-ups) developed in the vyayamshala schools of local Indian gymnastics.

Coincidentally, both B. K. S. Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois, who are major influences on modern yoga forms, themselves studied under teacher Krishnamacharya at the Mysore Palace in the 1930s. Sjoman further researched Krishnamacharya, finding several writings in the palace library. In addition, Sjoman discovered that the royal family, in the early 1900s, had employed a British gymnast to train the young princes. So, when Krishnamacharya arrived in the 1920s to start a yoga school, his schoolroom was the former gymnasium complete with ropes.

Krishnamacharya had full access to this Western-style gymnastics room in the Mysore palace with all its familiar ropes and other props that he began to incorporate into his yoga classes.

Sjoman copied a Western gymnastics manual written at the beginning of the 20th century that was available to Krishnamacharya. Sjoman argues that several exercises detailed in a purposely written western gymnastics manual were incorporated into Krishnamacharya's syllabus, resulting in his vinyasa style, and further passed on to Iyengar and Jois.

In addition, at the beginning of the 20th century, a system of training and gymnastic exercises without the use of gymnastic apparatus and simulators (using only the weight of the body itself as a load), developed by a Danish gymnast Niels Bukh (1880-1950), was introduced and popularized in India by the British and the Young Men's Christian Association "(YMCA). Historian Mark Singleton claims that thanks to the YMCA and gymnastics training in British India, Bukh exercises influenced Krishnamacharya's yoga style. Singleton states that "at least 28 exercises in the first edition of Bukh's manual are strikingly similar (often identical) to the yoga postures found in “Yoga Mala” (1958) by Pattabhi Jois and “Yoga Deepika: Clarifying Yoga” (1966) B. K. S. Iyengar". The connecting link here is again Krishnamacharya, whom Singleton calls "the main player in the modern fusion of gymnastic asana practice and the Patanjali tradition".

Sjoman's book, “The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace”, was published in 1996 and contained 122 asana illustrations from the Sritattvanidhi tract and excerpts from the Mysorean manual of Western gymnastics. Naturally, the radical, perhaps even heretical, idea that some of the practices of modern yoga as exercise is based on something as mundane as European gymnastics has caused a stir in the yoga world.

In 1940, Krishna Raja Wodeyar IV died, and his nephew and successor Jayachamarajendra (1919-1974) showed less interest in Krishnamacharya's yoga, and no longer provided support for publishing the texts and sending the groups of teachers to neighboring areas. After political changes in 1947, at a time when India gained independence, the powers of the maharajas were curtailed, and a new government arose. Funding for the yoga school was cut, and Krishnamacharya had to work hard to keep the school going. At the age of 60 (in 1948), Krishnamacharya was forced to travel a lot to find students and provide for his family. The Yogashala in Mysore was ordered to close at the behest of K. Chengalaraya Reddy, the first chief minister of Mysore, and the school was closed in 1950.

After leaving Mysore, Krishnamacharya moved to Bangalore for a couple of years, and then was invited in 1952 for permanent residence in Madras by a famous lawyer, who turned to Krishnamacharya for help in healing a stroke. At the time, Krishnamacharya was in his sixties, and his reputation as a strict and intimidating teacher softened somewhat.

In Madras, Krishnamacharya was recruited as a lecturer at the college. He began to have yoga students from different walks of life and a different physical makeup, because of this he needed to adapt the teaching to the abilities of each student. Throughout the remainder of his teaching, Krishnamacharya continued to perfect the individual approach that became known as vini yoga. Many considered Krishnamacharya to be a yoga master, but he continued to call himself a student because he felt that he was always practicing study, research and experiment. Throughout his life, Krishnamacharya refused to appropriate the authorship of his innovative ideas and attributed them to his guru or ancient texts.

Pattabhi Jois

In 1927, at the age of 12, Sri Krishna Pattabhi Jois lived in the same village (Kaushika) with Krishnamacharya and attended his yoga lecture and demonstration in the Hassan district, and, according to him, became his disciple the next day. As Jois said much later, for two years he practiced yoga daily according to the Krishnamacharya system. Jois never told his family that he was doing yoga. According to him, he got up early, went to training, and then went to school. Jois studied with Krishnamacharya from 1927 to 1929 in his village (according to him), and then in Mysore from 1932 to 1953.

According to B. K. S. Iyengar, Pattabhi Jois was appointed by Krishnamacharya to teach asanas in a children's Sanskrit school when Krishnamacharya's yoga school was opened in 1933, and (Pattabhi Jois) “was never (Krishnamacharya's) student on permanent basis".

Having borrowed a lot from the achievements of Krishnamacharya, Pattabhi Jois founded his own direction in yoga – ashtanga vinyasa. Mark Singleton writes in his book "Yoga Body: the origins of modern posture practice": "Although Jois has certainly added to and amended sequences, my informants for this (9th) chapter (as well as an early publication by Krishnamacharya himself) corroborate the view that an aerobic “jumping” system similar to that now known as Ashtanga yoga was indeed sometimes taught by Krishnamacharya during this period (alongside other, nondynamic modes of asana practice)". The Sanskrit word "vinyasa" means "to place (nyasa) [body parts] in a certain way (vi)", but in the context of ashtanga vinyasa yoga, it actually means a link between asanas, when the transition from one asana to another (or entrance into asana and out of it) is strictly regulated in relation to the movements of body parts and even the number of breaths. The sequence of asanas during the lesson is also rigidly defined. In 1948, Jois founded the Ashtanga yoga research institute at his home in the Lakshmipuram district of Mysore. In 1964, he added a yoga room to the back of the house.

In 1964, the Belgian André Van Lysebeth spent two months with Jois, studying the initial and intermediate series of the ashtanga vinyasa yoga system. Shortly thereafter, he wrote a book called J'apprends le yoga (1967, "Yoga Self-Taught"), which mentioned Jois and gave his address. As a result, foreigners began to come to Mysore to study yoga.

In the last years of Pattabhi Jois's life, his big house was a “conveyor belt” for the issuance of prestigious diplomas for the completion of courses by foreign hatha yogis. At the same time, in the courses of ashtanga vinyasa there was no meditation at all, there were only sequences of physical exercises. A monthly course (classes lasted less than 2 hours a day) cost was about $500 excluding accommodation and other expenses. However, they were often conducted by his grandson Sharath Rangaswamy, who continued to lead the courses after the death of Pattabhi Jois in 2009.

An obituary in the English-language weekly “The Economist” questioned Pattabhi Jois's adherence to the yoga principle of ahimsa (non-violence), writing that “a large number of Mr. Jois's students seemed to be constantly limping with injured knees or backs due to his "adjustments" in ashtanga vinyasa yoga courses when he tugged them abruptly, forcing them to sit in the lotus position, sit on a split or bend their back”. Pattabhi Jois' adjustments have been described as “overwhelming, fearful and extremely uncomfortable for students when they are pushed out of their zones of physical and psychological comfort in an often difficult, even dangerous asana”.

The direct actual contribution of Pattabhi Jois to hatha yoga is the creation of the direction of ashtanga vinyasa yoga, or rigidly regulated transitions from one asana to another, as well as a rigidly defined sequence of asanas during a lesson. An indirect factual contribution is the demonstration that even eight decades of consecutive years of hatha yoga practice do not allow one to transform consciousness enough to master at least the first part of Patanjali's ashtanga yoga – yama with its satya, ahimsa and brahmacharya. Not to mention the actual goal of yoga according to Patanjali, achieved by Lahiri Mahasai and other holy miracle-working yogis, who were not only highly moral, but also surpassed human nature.

The author of this article lived for some time near Pattabhi Jois's yogashala and communicated personally with him in his office, as well as with his students in 2006. Below are comments (1, 2) from YouTube (not mine) that well characterize the situation around Pattabhi Jois:

I met this man in Mysore – he stopped me in the street and asked why I didn't practice at his Shala. I told him I studied with B. N. S. Iyengar. He immediately vilified Mr Iyengar (this is not B. K. S. Iyengar). I took an immediate dislike to him and his attitude. He ran his classes in Mysore only teaching westerners and charging an absolute fortune by Indian standards to do so. He also avoided paying all taxes in Mysore through corruption and claiming his school was 'a research institute'. At that time, in the 1990's there were many stories circulating in Mysore about his inappropriate behavior, his constant molesting of female students, etc. Many of his students were in absolute denial about this claiming that he was 'opening them' and was beyond reproach. I could never understand how supposedly enlightened liberal women from California could give this man a pass, and delude themselves so thoroughly. His students would kiss his feet before every class – literally! It was quite clear that his actions were self serving and unsound. It is amazing how people can be fooled by false prophets – and end up living in a cult like reality denying what is happening to them – or in front of them. Anyone who questioned what he did was ostracized by his followers. These same students would sit around and complain about a desperately poor rickshaw driver who supposedly cheated them out of 10 rupees – yet never blinked an eye when Mr Jois demanded $400 USD per month to attend his classes. I paid 100 ruppees per month to attend Mr B. N. S. Iyengars shala. Don't get me wrong – the yoga taught by Mr Jois was and is very powerful – but it is not exactly what it is claimed to be. It is actually a combination of calisthenics, yoga asanas – and developed in the 20th century. It is not an ancient tradition as Mr Jois claimed. His story of finding the secrets of Ashtanga on an ancient document – which was then eaten by green ants – it laughable and reminds me of the founding stories of Mormonism.

Just to add: I lived with a lady who was studying with Mr Jois: he gave her a serious knee injury with one of his brutal 'adjustments' – when she could not practice for over a month he demanded that she continue to pay him while she healed. She left the school completely disillusioned. Some of his students told me that such 'openings' were deliberate and carefully done – I thought they were half mad. Another male student was summoned to Jois's office; Jois said that the students fees were due – but the student had already paid for that month. Jois simply denied it and forced the man to pay again – which he did – though he was very upset. Yet his devotion to 'guruji' was so strong that he accepted it as some sort of spiritual lesson! IDIOT. I also heard that Mr Jois would arrange the prettier ladies at the front of the class – and often totally ignore male students who were not long time followers. I am surprised that the stories about his inappropriate behaviors have only been talked about recently as I know for a fact they were common knowledge in Mysore over 20 years ago.

Even for Pattabhi Jois, who lived for 93 years, his 82 years of postural yoga practice was not allowed to work through even the first part of the eight-part yoga of Patanjali – the yama with its five components: non-violence (ahimsa; see here), truthfulness (satya; see the reproach of B. N. S. Iyengar), non-appropriation of someone else's (asteya; see ibid (satya) the story of a student whom Jois tricked into paying a second time $400 for a month of hatha yoga training), celibacy (brahmacharya; see the video about ahimsa from the very beginning) and non-acquisitiveness (non-accumulation, detachment; aparigraha; Jois created and developed for the rest of his life his own business project at a very expensive by Indian standards, and not only by Indian, teaching hatha yoga under the guise of a Yoga research institute). Needless to say, in the higher three parts of Patanjali's yoga – dharana, dhyana and samadhi – Pattabhi Jois could not demonstrate absolutely anything, not that he never achieved yoga realization, but even did not even try to at least begin to approach it. And even in his courses of ashtanga vinyasa, meditation was not taught at all (which did not prevent him from calling his fitness ashtanga vinyasa yoga, which, as it were, implies passing all eight parts – ashta-anga – of yoga). The life of Pattabhi Jois has become the best and most vivid example of the futility of ashtanga vinyasa and other postural yoga in the context of yoga realization according to Patanjali, as well as in the context of yoga in its understanding, which has dominated the last 5000 years, not counting the last 50 years of yogabiz.

B. K. S. Iyengar

Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar (1918-2014) was the brother-in-law (brother of the wife) of Krishnamacharya, while Krishnamacharya himself was Iyengar's son-in-law.

Iyengar's hometown, Bellur (then a small village) in Kolar district, Karnataka state, was severely affected by the Spanish flu pandemic at the time of his birth. He was the 11th of 13 children (10 of whom survived) born into a poor family to school teacher Sri Krishnamachar and Sheshamma. When Iyengar was five years old, his family moved to Bangalore. Four years later, a 9-year-old boy lost his father. Due to the effects of the influenza pandemic as a child, he grew up weak and sick, suffering from malnutrition and diseases such as malaria, typhus and tuberculosis.

At the age of 15, Iyengar moved to live in Mysore with his son-in-law, the famous yoga teacher Krishnamacharya. There he learned to practice asanas, which significantly improved his health. Over time, he was able to fully recover his poor health.

Krishnamacharya sent Iyengar and other students to demonstrate yoga at the Maharaja's palace in Mysore, which had a positive effect on Iyengar. Iyengar sees his connection with his son-in-law as a turning point in his life, stating that over a two-year period "he (Krishnamacharya) taught me for only ten or fifteen days, but those few days defined who I am today!" Pattabhi Jois argued that in fact it was he, and not Krishnamacharya, who was the actual teacher of Iyengar.

According to B. K. S. Iyengar, Pattabhi Jois was appointed by Krishnamacharya to teach asanas in a children's Sanskrit school when Krishnamacharya's yoga school was opened in 1933, and (Pattabhi Jois) “was never (Krishnamacharya's) student on permanent basis". At the same time, Pattabhi Jois claimed to be the teacher of B. K. S. Iyengar, although Iyengar himself denied this, and their hatha yoga systems are different, although both learned from Krishnamacharya.

A common feature of the teaching of postural yoga by Iyengar and Jois is the cruelty of their adjustments during classes and demonstrations of asanas by students, despite Iyengar's formal assurances in his books about the need for an extremely careful and accurate approach to the study of asanas. When someone reads from Iyengar about the need for extreme caution in the practice of asanas (for example, in Iyengar's book “Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health” on the 85th page: "Be careful to stretch your back and neck gradually"), remember these video clips with his adjustments. Or, more exactly, student abuse.

In particular, Victor Van Kutten (1 2) said in an interview: “A lot changed when Iyengar, trying to open up the upper back, broke my spine, which led to paralysis three days later... and the paralyses started, taking all I had away, even my voice, over the time of two weeks... It took me some half year to recover enough to make me feel comfortable in my profession as a yoga teacher. But I still have a limp, for my right leg never recovered totally. When a massage teacher who practiced Chinese martial arts and worked with Chi, checked me many years ago, in Calgary, said that, if I had not practiced Yoga, I would be in a very bad state, since the middle of the thoracic spine was blocked, not broken, but two vertebra were out of place and had fused... After that I could no longer follow the teachings of Iyengar...” On the same forum people write: “Iyengar did not deviate one iota from the principles of his teacher (Krishnamacharya). He also broke his students, and his son, Desikachar, writes about this "through tears of love".”

In this old video, Iyengar walks on the backs of female students, and in this case it is extremely difficult to comprehend how this very dangerous acrobatics brings them closer to the goal of Patanjali yoga.

In 1937, Krishnamacharya sent Iyengar to Pune to teach yoga at the college's sports club. In Pune, Iyengar perfected his practice by spending many hours a day learning various techniques, and experimenting with creating his own. As Iyengar's methods improved, more and more students came to him, and his fame began to spread throughout Pune and beyond.

Iyengar created his own direction in hatha yoga – Iyengar yoga. One of its characteristic features is the use of various props – supports and devices for those who still cannot perform certain asanas or hatha yoga exercises for health reasons. Props are a variety of rollers, stands, supports, belts, ropes, pillows and even chairs.

A characteristic feature of Iyengar yoga is the static performance of asanas with the necessary supports. Another characteristic feature of the method is a detailed explanation of each posture and an individual approach to each practitioner. According to Iyengar, his yoga involves the study of asanas and pranayama, which in this yoga include all the other higher parts (angas, often called steps; aGga in the Kyoto-Harvard encoding) of yoga, up to samadhi. But at the same time, there is none of the Iyengar yoga practitioners who would really achieve samadhi in meditation and yoga realization; however, the same applies to Iyengar himself, as well as to Pattabhi Jois, Krishnamacharya and millions of practitioners of postural yoga for the last half century. An important aspect of Iyengar yoga is the sequence of asanas. In all this, the influence of Krishnamacharya with his gymnastic bias can be traced.

In 1952, Iyengar met and became friends with the famous violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who helped him go to teach yoga in Europe: England, France, Switzerland and other countries. For the first time in history, a large number of Westerners became familiar with the practice of (postural) yoga. Gradually, yoga gained great fame in the West, which is largely due to Iyengar.

In 1966, Iyengar's book "Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika" was published, which became an international bestseller and was translated into 17 languages. This book, often referred to as the "bible of (hatha) yoga," played a key role in making (hatha) yoga famous throughout the world. In the book, he presented a detailed description of 200 yoga asanas, 10 pranayamas and 2 bandhas, and also gave his own definition of the main terms from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

Then Iyengar wrote books on pranayama and various aspects of yoga philosophy. In 1984, Iyengar officially stopped teaching yoga, but continued to be active in the world of Iyengar yoga, writing books. In total, he is the author of 14 books. Iyengar's daughter Geeta and son Prashant also gained fame as Iyengar yoga teachers. At the beginning of the XXI century, it was possible to go to their courses only 2 years after the date of application due to the huge queue, and the cost of monthly courses was several times higher than that of Pattabhi Jois.

T. K. V. Deshikachar

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya Venkata Desikachar (1938-2016), better known as T. K. V. Desikachar, was a modern yoga teacher and son of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. There are several significant modern approaches to hatha yoga in the West, which are based to varying degrees on traditional teachings, and which also exploit the therapeutic potential of yoga. The most traditional orientation of hatha yoga, which has the modern name viniyoga (vini means “application”, “using”), is found in the school of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya and his son Desikachar.

Desikachar was born in Mysore and moved to Madras (now Chennai) in the early 1960s. He studied engineering, but, inspired by his father's teachings, abandoned his engineering career and became his father's apprentice in 1960, although this was a time when the practice of yoga was not yet respected as it is today. Since the 1970s, he has taught many times in many parts of the world and has published many books that have become bestsellers, as a result of which his name and teachings became known throughout the world.

Desikachar is renowned for his incomparable ability to clarify (demystify) the teachings of yoga, as well as his pioneering work in the fields of wellness yoga and yoga therapy. During his thirty years of intensive training with his teacher, he learned the practice and application of all the tools of yoga, including japa (chanting of mantras), in order to be able to help people therapeutically and to help them live better and more productively in their daily life and develop spiritually. He also studied in detail many of the scriptures of ancient India. Thanks to this long period of study, Desikachar's teachings so closely and so fully reflect the tradition of his father.

Based on the teachings of his father, Desikachar continued to develop viniyoga. This highly individualized approach adapts the practice to the specific physical and mental state of each student, their emotional state, age, cultural background and interests. It is completely holistic, with all aspects of the practice related to yoga theory.

In 1976 Desikachar founded Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM), a Yoga Therapy Clinic and Yoga Center in Madras, as a non-profit public benefit foundation teaching yoga within India. Under the direction of Desikachar, KYM offered teacher training and personalized instruction in asanas, pranayamas, meditation, yoga philosophy and Vedic mantra chanting, as well as groundbreaking research on the effects of yoga on people with schizophrenia, diabetes, asthma and depression.

Viniyoga is a dynamic and gentle yoga practice that emphasizes an individual approach to the practitioner. The word "viniyoga" is mentioned in the Yoga Sutras in sutra 3.6 and is translated as "application", "action", and not the name of the yoga style. Viniyoga is based on the fabricated by Tirumalaya Krishnamacharya work "Yoga Rahasya" and is taught in India at the center "Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram", but on his website T. K. V. Desikachar himself asked in 1998 not to use the name viniyoga and not consider it as a separate teaching. In his book “The Viniyoga of yoga. Applying yoga for healthy living” Desikachar says that Viniyoga is not a style but a method of teaching yoga.

Although T. K. V. Desikachar, the son and disciple of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, is considered the founder of this yoga trend, Desikachar himself did not establish any style of yoga with a separate name.

A 2005 study showed that viniyoga practice can be effective in reducing pain and complications in patients with chronic back pain (lumbago). However, there is no evidence that viniyoga is much more effective in reducing back pain than stretching.

In 2012, Kausthub Desikachar, the son of T. K. V. Desikachar and grandson of Sri T. Krishnamacharya, has stepped down from the Krichnamacharya Yoga Mandiram and the Krichnamacharya Healing and Yoga Foundation in light of accusations of "sexual, mental, and emotional abuse," according to an email announcement sent by the foundation. The email said Kausthub has not denied the accusations and has cancelled his current teaching schedule.

Belonging to the parampara (tradition) of the teachers of postural yoga and the practice of postural yoga did not allow the grandson of Krishnamacharya and the son of Desikachar to pass at least the first part of Patanjali's yoga – the yama with its brahmacharya, satya and ahimsa, and this is the most vivid confirmation of the ineffectiveness of postural yoga of the tradition of Krishnamacharya and a demonstration that not only the practice of hatha itself is not effective in relation to the goals of Patanjali's yoga, but even belonging to the most famous parampara of hatha yoga teachers does not allow transforming the mind so much as to master at least the first part of Patanjali's ashtanga yoga – the yama with its ahimsa, satya and brahmacharya.

If we assess the prevalence of versions of current yoga in the West, then about 80% of all taught yoga in one way or another comes from B. K. S. Iyengar, about 15% – from Pattabhi Jois, and the remaining about 5% falls on the share of all other teachers and gurus put together.

What Krishnamacharya, Iyengar, Pattabhi Jois and their students have done with yoga can be called in different words. You could call it a yoga brand rebranding, restyling, or repositioning. Someone will call this a raider takeover of the "yoga" brand by three athletes (striving for worldly success, as the whole life story of each of them has shown) without higher education, and even without any specialized anatomical medical education, and he will be right too.

The point of view of what has been done with the concept of yoga over the past 50 years, especially in the West, will depend on the cognitive abilities of the evaluator, his knowledge of the history of yoga (and especially hatha yoga) and personal goals. A yogic acrobat with a "cool" certificate of Jois's yogashala (or even more expensive certificate of the Iyengar yoga school), which he got for a total of a couple of thousand dollars, may have one point of view, while a practicing chitta-vritti-nirodha yogi may have another. In addition, a whole generation has already grown up, which basically has not seen any other yoga, in addition to postural, and many of its representatives already insist on the "traditional" perception of yoga as a postural practice, even despite the complete absence of any mention of postural practices in "Yoga sutras" of Patanjali, which they have no time to read.

The complexity of yoga according to Patanjali, or Raja Yoga, is also in the fact that meditation is orthogonal to everything that the mind was doing before it (orthogonal: "perpendicular" to everything that was before; orthogonality in system modeling: the property of non-intersection, non-overlapping of the contents of integral system). Meditation is achieved by a certain release of effort, not by purposeful effort. Any rough attempt at meditation is doomed to failure in advance.

It is possible that the psychological rejection by many people of the required approach to meditation has led to the popularization of postural yoga in the world over the past 50 years, since in this nowaday fitness the new goals set (new complex asanas, stretching and everything else) are achieved by direct efforts, methodologically familiar to the routine mind.

In addition, meditation is much more difficult to sell than physical fitness, which has an incomparably larger reach and niche market. Many people will not understand what they are paying money for if they just sit and “do nothing”, since the real practice of meditation can remain out of the philistine paradigm, and the bottom line will be only sitting on the rug, especially if there is no objective control of the state of mind of the course visitors, for example, through the neuroheadsets, such as NeuroSky. And even the neuroheadsets do not help if a person still does not know how to meditate at all – such an untrained beginner skips the state of meditation so quickly and imperceptibly for himself that he does not understand what kind of state he should hold and train.

Because of all this, yoga, with its mystical halo, which served as free advertising in the West, has slipped over the past 50 years into physical training, given in physical sensations.

Below are selected excerpts from this article and some others:

Yogic asanas were never ‘Vedic’ to begin with. Far from being considered the crown jewel of Hinduism, yogic asanas were in fact looked down upon by Hindu intellectuals and reformers—including the great Swami Vivekananda—as fit only for sorcerers, fakirs and jogis.

The reality is that postural yoga, as we know it in the 21st century, is neither eternal nor synonymous with the Vedas or Yoga Sutras. On the contrary, modern yoga was born in the late 19th/early 20th centuries. It is a child of the Hindu Renaissance and Indian nationalism, in which Western ideas about science, evolution, eugenics, health and physical fitness played as crucial a role as the ‘mother tradition’. In the massive, multi-level hybridisation that took place during this period, the spiritual aspects of yoga and tantra were rationalised, largely along the theosophical ideas of ‘spiritual science’, introduced to India by the US-origin, India-based Theosophical Society, and internalised by Swami Vivekananda, who led the yoga renaissance.

In turn, the physical aspects of yoga were hybridised with drills, gymnastics and body-building techniques borrowed from Sweden, Denmark, England, the United States and other Western countries. These innovations were creatively grafted on the Yoga Sutras—which has been correctly described by Agehananda Bharati, the Austria-born Hindu monk-mystic, as ‘the yoga canon for people who have accepted Brahmin theology’—to create an impression of 5,000 years worth of continuity where none really exists.

There is no ancient brahminical lineage of hatha yoga. Agehananda Bharati (Leopold Fischer) was born in Austria and in 1951 left for Varanasi, where on the banks of the Ganges he was ordained by Swami Vishwananda Bharati to the monk of the Dashanami Sampradaya order, receiving the monastic name Swami Agehananda Bharati, and became the first full-fledged Western person who became a Hindu monk.

Contrary to the widespread impression, the vast majority of asanas taught by modern yoga gurus are not described anywhere in ancient sacred Hindu texts. Anyone who goes looking for references to popular yoga techniques like pranayam, neti, kapalbhati orsuryanamaskar in classical Vedic literature will be sorely disappointed.

The four Vedas have no mention of yoga. The Upanishads and The Bhagvad Gita do, but primarily as a spiritual technique to purify the atman. The Bible of yoga, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, devotes barely three short sutras (out of 195) to physical postures, and that too only to suggest comfortable ways of sitting still for prolonged meditation. Asanas were only the means to the real goal—to still the mind to achieve the state of pure consciousness—in Patanjali’s yoga.

There are, of course, asana-centred hatha yoga texts in the Indic tradition. But they definitely do not date back 5,000 years: none of them makes an appearance till the 10th to 12th centuries. Hatha yoga was a creation of the kanphata (split-eared) Nath Siddha, who were no Sanskrit-speaking sages meditating in the Himalayas. They were (and still are) precisely those matted-hair, ash-smeared sadhus that the HAF (Hindu American Foundation) wants to banish from the Western imagination. Indeed, if any Hindu tradition can at all claim a patent on postural yoga, it is these caste-defying, ganja-smoking, sexually permissive, Shiva- and Shakti-worshipping sorcerers, alchemists and tantriks, who were cowherds, potters and suchlike (i.e. not by brahmanas). They undertook great physical austerities not because they sought to achieve pure consciousness, unencumbered by the body and other gross matter, but because they wanted magical powers (siddhis) to become immortal and to control the rest of the natural world.

Quoting from here: In 1893, an Indian saint named Vivekananda came to the United States to attend the Parliament of the World's Religions, which was the part of the World Columbian Exposition, an early world's fair in Chicago. Vivekananda was a popular speaker during the exhibition and was even able to debunk some of the stereotypes about Indians that had formed in Western society. He talked a lot about religion and Indian national traits, but he did not mention yoga and did not perform asanas, because that would be considered unacceptable.

The fact is that most of the street performers and magicians practiced hatha yoga, which has been associated with religious fanaticism. Hatha yogis were located on the streets of India to make money, yet Western society did not know anything about this form of yoga until photography was invented, and until someone brought from India pictures of people sitting on the street in strange positions trying to get alms. But the truth was that all these postures were only a small part of the whole yoga; much more yogis focused on cleansing the stomach, for which they swallowed pieces of tissue, administered enemas; engaged in pranayama – breathing exercises; and performed mudras – special ritual gestures and hand positions.

Over time, Vivekananda turned a Harvard Street motel into a seminar center, and people from all over the coast became obsessed with his teachings on pranayama, meditation and positive thinking. Vivekananda publicly rejected hatha yoga and asanas – ideas about them are deeply rooted in the minds of people who associated them with the previously mentioned street ragamuffins.

Far from being purely Vedic, hatha yoga was born a hybrid. As Amartya Sen reminded us in his recent address to the Indian Science Congress, universities like Nalanda were a melting pot where Buddhist Tantra made contact with Taoism from China. By the time Buddhism reached China through Nalanda and other centres of cultural exchange along the Silk Route in the north and the sea route in the south, Taoists were already experimenting with qigong, which involved controlled breathing and channelling of ‘vital energy’. Taoist practices bear an uncanny similarity with the yogic pranayam, leading scholars to believe that the two systems have borrowed from each other: Indians learning exercise-oriented breathing from Taoists, and Taoists in China learning breathing-oriented meditation from their Indian neighbours.

But this Taoist-Buddhist-Shaivite synthesis was only the beginning. As we see below, hatha yoga was to absorb many more influences in the modern era, this time from the West.

FABRICATING ANCIENT TEXTS

The problem for historians of modern yoga is that even these medieval hatha yoga texts describe only a small fraction of modern yogic postures taught today. BKS Iyengar’s Light on Yoga alone teaches 200 asanas, while the 14th century Hatha Yoga Pradipika lists only 15 asanas, the "Gheranda Samhita" text of XVII century lists 32 asanas, and in the text of the same XVII (or XVIII) century "Shiva Samhita" names of 84 asanas are mentioned, of which only 4 are described in detail.

Given that there is so little ancient tradition upon which to stand, unverifiable claims of ancient-but-now-lost texts have been promoted. The Ashtanga Vinyasa system of Pattabhi Jois, for example, is allegedly based on a palm-leaf manuscript called the Yoga Kurunta that Jois’s teacher, renowned yoga master T Krishnamacharya (1888–1989), unearthed in a Calcutta library. But this manuscript has reportedly been eaten by ants, and not a single copy of it can be found today. Another ‘ancient’ text, the Yoga Rahasya, which no one has been able to trace, was supposedly dictated to Krishnamacharya in a trance by the ghost of an ancestor who had been dead nearly a millennium. Such are the flimsy—or rather fictional—grounds on which rest Hinduism’s claimed intellectual property rights to yoga.

This sorry attempt to create an ancient lineage for modern yoga is reminiscent of the case of Vedic mathematics. In that case, Swami Shri Bharati Krishna Tirtha, the Shankaracharya of Puri, insisted that 16 sutras in his 1965 book, titled Vedic Mathematics, are to be found in the appendix of Atharva Veda. When no one could find the said sutras, the Swami declared they appear only in his own appendix to the the Atharva Veda and not any other! This ‘logic’ has not prevented Vedic maths from emerging as a growth industry, attracting private spending by well-heeled Indians seeking to boost brainpower and public spending by state governments that have introduced it in school curriculums.

It should also be noted the great contribution to the development and spread of yoga in the world, which was made by Swami Sivananda of Rishikesh, who founded the Divine Life Society in 1936, and his outstanding student Swami Satyananda Saraswati, who founded the Bihar School of Yoga in 1964, but they promoted yoga without bias towards hatha yoga, and that's a completely different story.

In fact, yoga as meditation consists of a very long, decades-long daily routine practice of shamatha / samadhi meditation and other techniques (e.g. vipashyana / samyama) based on it, along with the observance of the moral principles of yama and niyama. A certain muscle tone is really necessary in order to comfortably sit for half an hour or 3 hours in meditation in one position. But the transformation of inherently preparatory physical exercises into an independent cult resembles the situation of repeaters who cannot move to the next class in any way.

Despite the millions of people who have practice hatha yoga all over the world for the last half century, there is not a single yoga-realized saint who would achieve the goal of yoga through this physical gymnastics, or at least after mastering hatha yoga. Moreover, observations show that the practice of current yoga, even for decades, does not improve consciousness. Pattabhi Jois and many teachers of yogabiz serve as an example of the zero effectiveness of current yoga in relation to the declared (spiritual) goals. Despite all their practices and shatkarmas, their consciousness does not become truly purified of vices, and they do not become truly moral persons, remaining immersed in the vanity of yogabiz with the substitution of concepts. In fact, today's yoga (if not to damage the joints in the classroom, which in reality is rare) promotes longevity and preservation of mobility in old age, but the same is provided by Pilates and sports.