|

You are on the page: Scriptures.ru ➤ Meditation book ➤ What meditation is and how to meditate

|

What meditation is and how to meditate

Meditation is one of those concepts that seem to be something rather vague. In the minds of spiritual seekers, there are many different opinions about what meditation is. This article attempts to clarify this from a linguistic, historical and scientific points of view.

The very word "meditation" is of Western origin and comes from the Latin “meditation”, more precisely from the verb “meditari”, which in different contexts means “to think”, “to contemplate mentally”, to “develop ideas”, but its main meaning is “to think”.

In the Old Testament hāgâ (Hebrew: הגה) means not only to sigh or murmur, but also to reflect, to think, mentally contemplate. When the Torah was translated into Greek, “haga” was translated as “melete”. In the Latin Bible, haga / melete was translated as “meditatio”. The use of the term meditatio as part of a formal, stepwise process of meditation goes back to the 12th-century Carthusian monk Guigo II.

Further in Catholicism the idea of "meditation" is gradually filled with prayer content. In the future, there was a religious simplification and ritualization of that mental process, which was once quite a definite practical psychotechnical activity. The words "miraculous", "divine," "absolute," and so on were added to the description of meditation, although in the original sources there was no such a context.

Since the 12th century, the western term "meditation" has gradually been diluted and distorted, and now it is misleading that meditation is a dreaming, listening to pleasant music with the sounds of nature or a prayer. Although even in ancient, religious interpretation, meditation was a certain mental process.

Later the term "meditation" was logically applied as a translation of the name of eastern spiritual practices, called in yoga as "dhyana" and "samadhi", in Tibetan Buddhism – "shamatha", in Chinese Buddhism – "chan", in Japanese – "zen". The essence of the Dzogchen teachings of the oldest school of Tibetan Buddhism, nyingma, also, if we discard small doctrinal differences, generally corresponds to the same state of meditation as those listed above.

|

A Detailed Guide to Meditation Practice |

In the East, meditation is primarily understood as dhyana. This is the Sanskrit word for the seventh stage of the eight-step raja yoga, which is based on the "Yoga Sutras" of the holy sage Patanjali and refers to Hinduism. The term "raja-yoga" is a retronym introduced in the XIV century in "Hatha Yoga Pradipika" to establish the difference between a school based on the "Yoga Sutras" and a new movement in Hatha Yoga. Until the 14th century, yoga meant what is now called raja yoga, and until the 9th century, hatha yoga was not known.

In Buddhism, with its variety of meditative techniques, the yogic samadhi is most consistent with shamatha (in Sanskrit). In the Pali language, “shamatha” is called “samatha”, in Tibetan – “shyiné” (“shine”). The Sanskrit word "dhyana" corresponds to the Pali word "jhana", which also means meditation. In Buddhism, there is a classification of four successive material (with objects) jhanas (states of meditation in samadhi) and the following four non-material (objectless), through which the meditator passes during the practice of shamatha. Dhyana (Sanskrit), jhana (Pali), samten (Tibetan), chan (Chinese), son (Korean), thien (Vietnamese), zen (Japanese) are all different names for the same psychotechnique of meditation, which can be interpreted as the initial stage (or separate 8-9 stages) of shamatha.

It is dhyana and shamatha that are the basis of a great variety of different techniques in yoga and Buddhism, which are also called meditations for lack of other lexemes in Western languages of Western cultures, in which there was no spiritual quest on such a scale as in the East. But even in the East, the lexemes that appeared to describe spiritual practices were distorted over time to the point of losing their basic meaning, all for the same reason of the extreme small number of really practicing yogis in society, when a lack of understanding of their essence led to all sorts of speculation and false interpretations. As an example of such lexemes with practically lost initial meanings, we can cite the words "chitta", "dhyana" and others. In the Yoga Sutra alone, the lexeme "chitta" is used in several different meanings, and one way of explaining this is that this text has been added and edited many times by different authors in different periods of time. Additional difficulties with understanding the ancient texts of yoga, in addition to the ambiguity of the initial meanings of many key lexemes, are created, for example, by paronyms and other linguistic nuances, which modern linguists are not always able to correctly interpret. The flexibility of Sanskrit allows not only to actively play with the nuances of meanings, but also requires a good knowledge of the initial meanings of lexemes, which has been largely lost over the past couple of thousand years.

It is the extreme paucity of practicing yogis in the East and the practical absence of systemic meditation as a psychotechnique in Western cultures that created the problem with the generally available understanding of its essence.

In yoga in the West, meditation traditionally includes such continuations of dhyana as samadhi and samyama. In addition, various lesser known practices of individual directions of Hinduism are also included in meditation, although they are not only quantitative (in duration), but also qualitatively different from dhyana. In India, all these subsequent steps and practices have only their Sanskrit names, or they are derived from Sanskrit – without using words such as meditation or dhyana. Although samyama looks like a meditation, it can only be called so to please Western students. For Indian yogins, samyama is samyama, not abstract meditation. Attempts to call samyama and other complex practices as meditation are similar to as if a geologist would call all minerals simply as stones.

In Buddhism in the West, such practices as vipassana (in the Pali language, in Sanskrit – vipashyana (vipaśyanā), in the Tibetan language – lhagtong), metta (psychopractice of loving kindness) and numerous visualizations are traditionally also referred to meditation. At the same time, these practices are more diverse and more complex than a simple shamatha, but in reality they are effective and truly applicable only after reaching a full 3-4-hour shamatha. For Buddhists, all these practices have their names in Oriental languages, and the "generalized" abstract term "meditation" by Tibetans, Burmese or other Eastern non-English speaking Buddhists is not used.

This is similar to how Indian Hindus do not use the Western term “Hinduism”. The term "Hinduism" appeared only at the beginning of the XIX century, and the Hindus call their religion "sanatana-dharma" (in Sanskrit).

Interestingly, the Buddhists of the East call their religion "dharma" (law, teaching) or "Buddha-dharma" (Buddha's teaching). The term "Buddhism" was coined by Europeans in the 19th century.

|

Looking at all this leapfrog with the Western names of Eastern concepts, it becomes clear that it is useless to investigate the meaning and origin of the Western word "meditation". Instead, it is needed to explore such concepts as "dhyana" or "shamatha".

If you look at the dictionaries, then the problem is that all the available Sanskrit dictionaries were compiled by mleccha-Europeans, and not before the XIX century. The first and most famous Sanskrit-English dictionary was compiled by Monier-Williams, first published in 1872 and reprinted in 1899.

Sir Monier Monier-Williams became a professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University in 1860. In this post he actively advocated the preaching of Christianity in India, stating that one of the goals of Oriental studies as a science was to be the conversion of Hindus into the Christian faith. In his book "Hinduism" Monier-Williams predicted the early termination of the existence of Hinduism and called on Christians to stop the invasion of Islam. Given the views of the British sir on Hinduism, it is difficult to fully trust the translation of the Sanskrit word “dhyana” in his dictionary.

If you enter the word “dhyAna” (“dhyana” in the Sanskrit Kyoto-Harvard Convention) in the online dictionary of Monier-Williams, then it will be translated as "meditation, thought, reflection, (especially) profound and abstract religious meditation". Not only that, but now there is a pizza effect, when many Indian Indologists (followed by foreign ones a second time) already claim that dhyana means “thinking”. Although the analysis of verses 3.1 and 3.2 of Patanjali's Yoga Sutras raises at least strong doubts about this meaning of this Sanskrit word, especially in the context of verse 1.2.

If you enter the word "zamatha" ("shamatha" in the Kyoto-Harvard Convention), then it will be translated as "quiet, tranquility, absence of passion".

After reading the translations of the words "dhyana" and "shamatha", the essence of meditation does not become clearer.

If you enter the word “samadhi” in the Sanskrit-English Monier-Williams dictionary, then you get a set of derived values such as "wholeness, completeness" and even "tomb of a saint" instead of the literal meaning of this word. The word "samadhi" consists of two Sanskrit words "sama" and "dhi". "Sama" literally means "equal", "same", "equilibrium", "equidistant from extremes". The Sanskrit word "dhi" has many meanings and is used in a large number of complex words. Among its meanings are mentioned 'understanding', 'reflection', 'religious thought', 'mind', 'design', 'intelligence', 'opinion', 'meditation', 'imagination', 'notion', 'intellect'.

The Sanskrit word buddhi means “insight”, “intelligence”, “sapience”. Interestingly, "buddhi" is traditionally incorrectly translated as "intellect", as interpreters in context understand that it is something higher than the "manas"-mind (and is often referred to as something separate from the mind) but there is no exact equivalent in worldly Western languages for the concept of "buddhi". In English, the suitable equivalents for buddhi is the sapience, wisdom, acumen, gumption or sagacity. At the same time, the intellect is an aspect of the still inert mind, albeit the supreme one (of mind). Buddhi corresponds to the fourth body (vijnanamaya-kosha), while the mind to the third (manomaya-kosha). Vijnanamaya-kosha and anandamaya-kosha (the fifth body of the five) are built by meditations and other things, and provide further (in comparison with the mode of life of the median human being) the development of the soul and consciousness.

In other words, the state of samadhi is the state of a balanced consciousness. It is the tightrope-walking of consciousness, when it resides in equilibria, not skipping a balance and not falling into one of the extremes. This is a state in which the mind stays only as a "transparent" observer, without coloring by its activity the perception of the world around it and not labeling with its own meanings. Naturally, for a long stay in this state it is necessary to train a lot.

In Tibetan, the word gom (གོམས་ in Tibetan) is the most commonly used word for meditation. The meaning of this word completely coincides with the meaning of the Sanskrit word abhyasa (अभ्यास in Sanskrit in Devanagari; abhyāsa). The literal translation of the Tibetan word "gom" and the Sanskrit word "abhyasa" is based on the root "repetition" and means "exercise", "regular practice", "gaining skill", "training". The Tibetan word "gom" in its meaning is in a sense closer to the Sanskrit word sadhana (साधना in Sanskrit in Devanagari; sādhanā), meaning "a means to achieve [the goal]", and not to the words samadhi or dhyana, meaning meditation itself. Thus, the etymological analysis of the Tibetan word "gom" shows that this word indicates not the essence of the process or state of meditation / dhyana, but a characteristic feature of this process, and demonstrates that meditation is primarily a skill. And although the indication that meditation is just a skill and not a talent is a very important and encouraging moment for beginners in meditation, the meaning of the Tibetan word "gom" for meditation does not reveal its technique and the essence of this state, in contrast , for example, from the Sanskrit word samadhi.

However, in the Tibetan language there are two more, albeit more rarely used, but more accurate words to denote the stages of meditation. One of them is samten བསམ་གཏན, and it corresponds to the Sanskrit dhyana, or the 7th part in Patanjali yoga. Samten means to experience a stable (unshakable) state of mind. The second rarely used Tibetan word for meditation is tingedzin ཏིང་ངེ་འཛིན་, and it corresponds to the Sanskrit term samadhi, or the 8th part of Patanjali yoga. Ting in Tibetan means depth. Tinge, a now-ingrained altered pronunciation, means the ability to unwaveringly experience the depth of the mind. Dzin means "to hold," that is, to be able to hold an unshakable state of experiencing the depth of the mind. The samten and tingedzin psychotechnics have various additional internal levels of meditation practice.

If you turn to the scriptures, then the most authoritative and the most ancient text on yoga and meditation – "Yoga Sutras" of Patanjali. Below are the selected quotes:

1.1. So, this is instruction in yoga.

अथयोगानुशासनम्॥१॥

atha yoga-anuśāsanam ॥1॥

1.2. Yoga is the curbing (taming) of the vritti (agitations, unrest, disturbances) inherent in the mind.

योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः॥२॥

yogaś-citta-vr̥tti-nirodhaḥ ॥2॥

1.12. It (mental unrest) is hampered by practice and detachment.

1.13. Abhyasa (practice) is the effort necessary to ensure the calm of the unrest of the mind.

1.14. This practice will be successful with constant reverence, continuous for a long time.

1.34. At your choice, the balance of the mind can be obtained even by exhaling and delaying prana (breathing).

1.35. Or mental calm is caused by the activity of higher feelings.

1.36. Or [by contemplating] the inner light (jyoti) that is free from suffering.

1.37. Or the mind chooses as an object for the concentration those who do not have desires.

1.38. Or, depending on the knowledge of nocturnal dreams.

1.39. Or, if desired, through meditation (dhyana).

1.41. When the disturbances of the mind are under control, the mind becomes like a transparent crystal and acquires the ability to assume the form of either the cognizing, or the act of cognition, or the object of cognition.

1.44. Thus, meditation and supermeditation (nir-vicara) are described, which has its object subtle.

2.45. Samadhi (awareness) can be achieved by making the Lord the goal of all actions.

2.46. Asana, the pose, should be stable and comfortable.

2.47. The key to success in this regard is practice with effort, which becomes progressively easier, combined with deep contemplation (samapatti).

2.54. Disconnection (pratyahara) is that through which the senses do not come into contact with their objects, but follow the nature of the mind.

3.1. One-pointedness (dharana) is the unshakable mind.

देशबन्धश्चित्तस्य धारणा॥१॥

deśa-bandhaḥ cittasya dhāraṇā ॥1॥

3.2. The continuation of this mental effort is meditation (dhyana).

तत्र प्रत्ययैकतानता ध्यानम्॥२॥

tatra pratyaya-ikatānatā dhyānam ॥2॥

3.3. This meditation, when there is only the awareness of the object of meditation, but not the interpretations of the mind, is samadhi.

तदेवार्थमात्रनिर्भासं स्वरूपशून्यमिवसमाधिः ॥३॥

tadeva-artha-mātra-nirbhāsaṁ svarūpa-śūnyam-iva-samādhiḥ ॥3॥

3.4. The three together (dharana, dhyana and Samadhi) constitute samyama (exercise in self-control).

3.5. After mastering this (self-control) comes prajna (light of wisdom).

From all that is quoted it is clear only that meditation is the next stage of a certain mental effort after attaining the unshakable mind, that is, absence of thoughts.

At the same time, stanza 1.2 is the key one in the Yoga Sutras and in all yoga before its transformation into postural acrobatics over the past half century. It is chitta-vritti-nirodha, or curbing the agitations of the mind, that is the essence of meditation – such mental exercises as dhyanas and shamatha of Tibetan Buddhism (jhanas and samatha in Theravada), Chan of Chinese Buddhism, Zen of Japanese Buddhism, Dzogchen of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism and other similar self-development practices in which the mind must be kept pure and clear.

These formulations themselves, moreover, strongly resemble the shamatha of Buddhism, both verbally and in the context of their positioning as a methodological equivalent in place of this most important stage – one of the two main psychotechniques of Buddhism, along with vipashyana. In Buddhism, as is well known, in the state of shamatha there is not and cannot be any thoughts. At the same time, both the goal (many hours of samadhi state) and the object of application of efforts (the human mind) in both cases (yogic dhyana / samadhi and Buddhist shamatha with its jhanas / dhyanas) are the same, which implies the inevitable uniformity of the instrumentation, that is, the essence of the used psychotechniques (because the anatomy of the body and consciousness – it is the same anatomy of the body and consciousness in Africa). Thus, the essence of dhyana and samadhi can be clarified both through a linguistic analysis of the yoga texts themselves (and, first of all, the Yoga Sutras, this key text of Raja Yoga), and "on the other hand" – through comparing them with the corresponding stages of Buddhist practices, which, in turn, descended from the then yoga.

Due to the ambiguity and great vagueness of the meanings of many key lexemes of yoga and the understatement of the text of the Yoga Sutra (like the understatement of the Brahma Sutra), its interpreters – both ancient and modern – can attract its meanings in any desired direction, choosing in the dictionary the necessary meanings of lexemes that were previously attracted and distorted by Western linguists, and then building complex sophisticated constructions to substantiate their point of view. At the same time, you can find out the essence of the practices of Raja Yoga by comparing them with the practices of Buddhism, which was copied from the early version of yoga.

Just as it is impossible to practice samyama without first mastering the dhyana & samadhi, so it is impossible to practice dhyana without first attaining the state of absence of thoughts. Because the wording “the unshakable mind” even at the stage of dharana (preceding dhyana) eliminates the possibility of thoughts flickering. And the continuation of such a mental effort, which implies an improvement in the quality of this process, i.e. a better state of absence of thoughts (in Buddhism, this improvement in the quality of meditation is described as 8-9 jhanas), is called dhyana in verse 3.2. In verse 3.3, the interpretations of the mind mean the labeling and patterning by the mind, and the awareness means the direct perception or experience of the object of meditation.

Absence of thoughts, of course, does not automatically mean a state of meditation, but without it meditation for beginners is impossible. Absence of thoughts is easy to train at any time, when there is no need to talk or think, and, of course, when you remember about this training 😃. This can be done dozens of times during the day, and this is one of the most effective approaches to train the silence of the mind and the preparatory stage of meditation. In addition, absence of thoughts has its own levels of subtlety, which also affect the level of meditation attained.

In addition to absence of thoughts, it is necessary that "the mind becomes like a transparent crystal", that is, it was not engulfed by any unrest and kept the clarity of consciousness. The blunted state of consciousness, which in Buddhism is called the "sinking of the mind" (predrowsiness), does not allow a tired or drowsy mind to be in a state of meditation. In such a state, absence of thoughts is possible, and even some blunted form of self-control is possible to track the absence of thoughts, but a sleepy, almost sleeping mind can’t remember what is happening for longer than a few seconds, and this is definitely not meditation. In Sanskrit, the terms nimagnata (nimagnatā), nimagna (nimagna), laya (laya), samsidamana (saṃsīdamāna), samsidan (saṃsīdan), and the Tibetan language commonly uses the word བྱིང་བ་, which is pronounced "jiṅva" (with nasal "n") and literally means "drowning". “The 'sinking' of the mind gives a very pleasurable feeling, and many meditators do not want to disturb this feeling of bliss and calmness... If the meditator continues with his exercise during this particular condition of mind he will find that, after his concentration is finished, his body also carries this sinking feeling and then he just wants to sit idle and relaxed. Many people like this sort of feeling, but it is not the real samadhi, nor will it ever lead to that state. Therefore, however blissful and pleasant the experience may be the meditator must struggle out of it and get on with real meditation” – Samdhong Rinpoche. "Drowning the mind" is accompanied by a significant increase in theta and delta brain rhythms, while shamatha / samadhi meditation is characterized by a strong dominance of the brain alpha rhythm, especially in the 8-10 Hz range, over all other rhythms in absolute values of microvolts.

The excitement of the mind also hinders meditation, because in this case the stream of thoughts and various unrest in the mind becomes too pushy. Buddhism has its own advices for such cases. For example, with drowsiness, you should look down, and when excited – up (even if you meditate with your eyes closed). In addition, nothing prevents a person from thinking and being distracted with a dull (drowning) mind, while simultaneously violating both requirements of shamatha / samadhi meditation.

Meditation is like an exercise in equilibrium. In addition to the basic requirement of absence of thoughts, meditation is a subtle mental balance between an agitated and pre-drowsy mind. In a balancing act, you have to learn to notice the subtle moment of balance, and learn to maintain this balance with minimal efforts, because they are most effective, least costly energetically, and provide the best balance. Mastering meditation is very much like training an equilibrist, but instead of maintaining the balance of the physical body, a balanced state of the serene mind is maintained. Just as you can not immediately learn to walk on a rope, so mastering meditation requires a long training. Beginners constantly skip a balanced state of a serene mind, which is interrupted by thoughts, emotional instability or mental fatigue.

If we consider absence of thoughts (as one of the properties of dharana) as a prerequisite for meditation, then a further transition through long practice to an even subtler state of absence of thoughts (“absence of thoughts-2”), or a truly clear and unshakable state of mind on a subtler and deeper level of self-control, means the transition to the state of meditation itself. In the Yoga Sutras, this is dryly stated as follows: “3.2. The continuation of [this] mental effort is meditation (dhyana).” And although this definition is rather vague, it is really difficult to say more precisely. To attain the state of meditation, it is actually necessary to do once again what was practiced at the dharana stage, only at a subtler level of self-control, ensuring even greater purity of mind. As the state of meditation in a prolonged form at all times was available only to the smallest part of Indian society, even in Indian languages, due to the lack of demand in the society for such terminology, the semantic concepts, which could be used to describe the state of meditation completely and accessibly, were not formed. The definition given in the above quotation from the Yoga Sutras describes the state of meditation beautifully and simply, but at first it can be confusing to be uninformative, and it becomes really understandable only after a long practice of meditation. In addition to the qualitative absence of thoughts of the mind without any intentions and fluctuations-modifications in it, the state of shamatha meditation implies a certain degree of natural (laid-back, detached) composure and alertness of the clear mind, which should not be rude and excessive.

It should also be drawn the parallels between yoga and Buddhism in relation to the content of the stanzas 3.4 and 3.5 of the Yoga Sutras. With a detailed study of the essence of real Buddhist vipashyana-insight, it turns out that its practice without the already achieved continuous 3-hour shamatha is just as impossible as the practice of samyamas without achieving samadhi in yoga. Over the past 2500 years, controversial layering of various meanings has appeared in Buddhism, and they concern, for example, not only the cargo cult of the prayer wheel, which appeared almost a thousand years after the Buddha's departure as a result of a primitive frontal interpretation of the famous Buddhist expression "turnings of the wheel of dharma". Vipashyana (vipassana, by the way, extremely weakly expressed in the original Pali canon) was subsequently interpreted in simple words as analytical meditation, and then in Buddhism, apparently, the backward idea spread that the thought process of thinking & consideration in the process of "analytical meditation" is supposedly vipashyana. Then, predictably, the idea arose that such a "vipashyana" could be practiced even before reaching the 3-hour shamatha. But the fruits of such "analytical meditation" will not be instant insights into the essence of things at the level of clairvoyance, but just ordinary logical conclusions and inferences obtained with varying degrees of accuracy and reliability. It should be noted that the Sanskrit word vipashyana was translated into Tibetan as "lhattong" – "divine, or supreme, vision", and therefore such an ability cannot be expected from an ordinary untrained mind without attaining 3-hour shamatha. Correct ideas about what vipashyana is and what exactly is meant by "analytical meditation" have been preserved, for example, in the Nyingma school ("old translations") of Tibetan Buddhism. In particular, such meanings were voiced by Sangnak Tenzin Rinpoche.

It should be noted that the formation of vipashyana as a separate psychotechnique and a kind of meditation began only in the 4th-5th centuries as a result of the activities of the Mahayana Buddhist thinker Asanga (4th century) and Theravada Buddhist thinker Buddhaghosha (5th century, author of the "Visuddhimagga" treatise). In early Buddhism, when describing the eighth stage of the noble eightfold path - samyak samādhi, or "correct concentration", which means the psychotechnics of shamatha, vipashyana was not yet a separate psychotechnique.

Among beginner meditators, especially in the West, and those who are familiar with meditation only theoretically, the notion that meditation is a kind of utter relaxation of the mind, a kind of “maximum sinking to nowhere,” is quite common. But this is not true. Such relaxation can help relieve stress in a bustling metropolis, but this is not meditation. In addition, such “sinking" often leads to a "drowning of the mind" and a drowsiness, which means the end of the waking state, and also has nothing to do with meditation. In Buddhism, there are absolutely definite indications that meditation implies a certain self-control and a certain watchful state of the observer, which, however, does not label what is happening. Moreover, in Buddhism, shamatha meditation is often called concentration (meaning vigilant awareness of a clear mind). Of course, this is not a concentration in the usual sense of the word, but also not a mental "sinking to nowhere".

Quote from the book "Buddhist meditation" by Samdhong Rinpoche:

The 'sinking' of the mind gives a very pleasurable feeling, and many meditators do not want to disturb this feeling of bliss and calmness. Besides this, the mind, although still concentrating on the picture, has yet imperceptibly lost its energy and clarity and has become dull like stagnant water with scum on it. If the meditator continues with his exercise during this particular condition of mind he will find that, after his concentration is finished, his body also carries this sinking feeling and then he just wants to sit idle and relaxed.

Many people like this sort of feeling, but it is not the real samadhi, nor will it ever lead to that state. Therefore, however blissful and pleasant the experience may be the meditator must struggle out of it and get on with real meditation.

There is another extreme in the concept of what meditation is. Some visitors and even teachers of meditation and yoga courses are very tense during meditation. This approach is especially common in India. They "heave" with all their might, with a very noticeable grimace. This is a relatively massive phenomenon. And this testifies to the fact that the tradition of meditation has been largely lost in the “consumer goods” yoga courses of many teachers in India, because these teachers, being simply artisans of their profession, often insist that this is supposedly the right method of meditation, reducing it to a primitive ultimate concentration. Apparently, this is how they understand the “one-pointedness of the mind” in dharana concentration and “the continuation of this mental effort” (Yoga Sutras 3.1-2), believing that meditation is supposedly even greater (tense) concentration. Of course, this is not so.

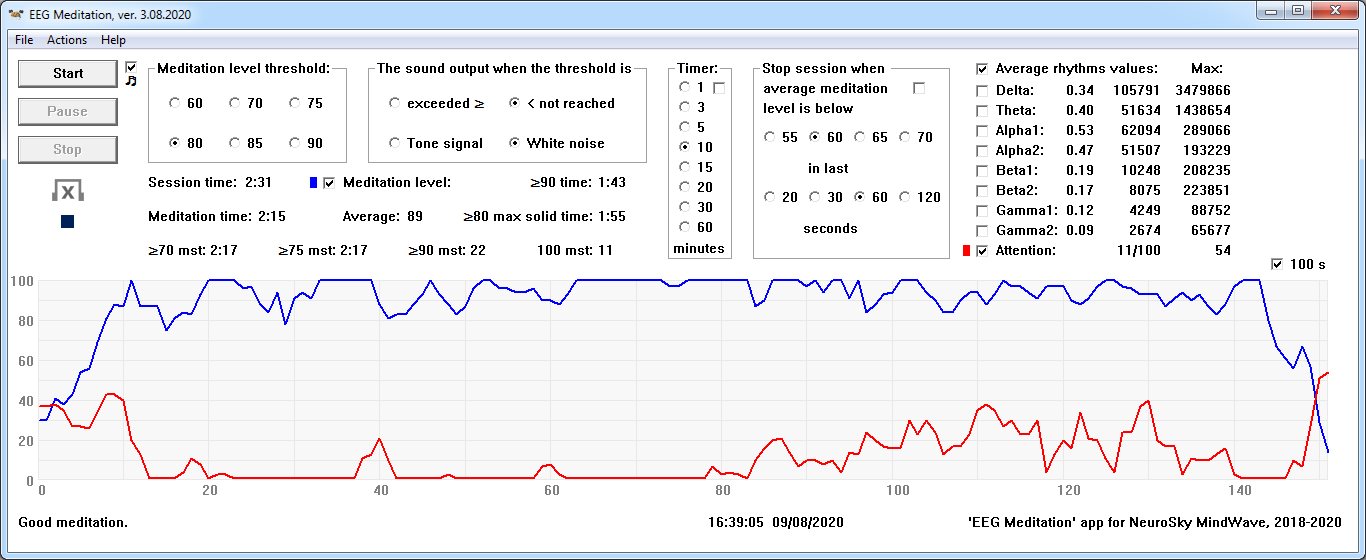

The chart below for a shamatha meditation session with the NeuroSky MindWave Mobile 2 neuroheadset (the "meditation" parameter of which is calibrated for shamatha) and the free EEG meditation application for Windows (there are also free versions for Android and iOS) clearly shows that meditation is not concentration. On the screenshot you can see a blue graph of the level of shamatha meditation and a red graph of the level of attention (concentration), which is also determined by this headset. Despite the fact that the meditator must first master the ability to concentrate (many already have this skill) in order to then proceed to meditation, in the state of meditation itself there should be no coarse concentration. In correct shamatha meditation there is only a slight sense of composure, devoid of any obvious concentration. The state of consciousness in shamatha meditation should be natural and unclouded by any intentions of the mind, not to mention the need for the absence of explicit thoughts.

|

Also, taking into account current trends in yoga, it is necessary to clarify sutra 2.46. The Sanskrit word "asanam" (āsanam) is formed from the root "ās" – "to sit" (āsa) – by adding the suffix -ana, which gives the sense of action to the original meaning. That is, asana is a "sitting" or sitting position. In this sense, the "standing asana" phrase is an oxymoron that arose after numerous modifications of the original meaning of the word. The same applies to other asanas in which the yogi does not accept a sitting position. Here we cannot but recall the naturalist Cratylus, who argued in a dispute with the conventionalist Hermogenes that the words reflect the "natural similarity" between the form of the word and the thing depicted by it. In addition, in the Yoga Sutras there is a clear definition of asana:

sthira-sukham āsanam ॥46॥

46. Asana is that which possesses [properties] of stability and pleasantness.

As we can see, already in this very definition there are no moments of the training approach and body loads. It is unlikely that it will be possible to improve muscle tone or stretching, while staying in a comfortable and pleasant position. In addition, Patanjali does not indicate an exact variant of the position of the body, since the origin of the “asana” lexeme clearly indicates that this is a sitting pose, and the author of the Yoga Sutras did not consider the remaining details important enough to describe them. If you start from logic, then, from his point of view, they are not significant. One well-known distinctive feature of sitting postures in which you can be comfortable for a long time is a straight back.

In fact, everything depends on your regular training and perseverance. Meditation is not something that you can learn in a couple of days or say that you have already mastered it as much as possible. Like trying to learn to play guitar or training with collapsible dumbbells, a tangible result will appear only after years of persistent training. At the same time, too intense efforts in meditation are as meaningless as abrupt efforts to keep the balance on the rope.

|

The ability to meditate is primarily a skill. Meditation is an interesting pristine state where the mind, for example, naturally withdraws from both labeling and even the idea of detachment from labeling. This is beautifully said in the above-mentioned book "Meditations" by J. Krishnamurti. Moreover, the more you advance in the meditation skill, the more intensively and more you will have to practice for further progress.

In the Eastern tradition, it is believed that a teacher is highly desirable for studying meditation. In past times, one could find out how to learn to meditate, only from a teacher, or from very rare the then books if there are certain innate abilities for meditation. As a result, the requirement of the need for a teacher for any disciple who wanted to study meditation has almost become a dogma.

Nowadays there are new facilities for studying meditation. The scientific approach and studies of commonly recognized meditation masters with the help of electroencephalographs and fMRI enabled to learn interesting features of meditation. It turned out that it is characterized by a decrease in the beta-rhythm of the brain and an increase in alpha rhythm, and, with case of continued training in meditation, also an increase in theta rhythm.

For the last 10 years, relatively cheap "household" versions of electroencephalographs have appeared that allow not only to track individual brain rhythms in the home, but also to show the presence of meditation itself. NeuroSky's EEG headsets were developed after extensive research of genuine meditation masters, including Tibetan monks, and show your level of meditation every second.

EEG headsets are revolution in the study of meditation. They provide one more way to study it, in addition to the teacher and the text guide. The ready-made parameter "level of meditation" allows you to track the moments of entering the state of meditation, which previously could not be noticed by the disciple, and this can greatly accelerate the study of meditation. In addition, absence of thoughts does not guarantee the presence of a state of meditation ("absence of thoughts-2.0" in the absence of "drowning the mind"), and NeuroSky neuroheadset with the "meditation" parameter shows this difference excellently and uncompromisingly.

With the help of EEG headsets, you can faster master the basic dhyana, and in the distant future even shamatha, and then go on to various subsequent practices described in yoga and Buddhism in which dhyana and shamatha are used as a necessary basic requirement.

The author of the article also tested the effect of binaural beats in practice in real time using the NeuroSky neuroheadset. Various experiments with different recordings of alpha rhythms, played at different volumes for about 10 minutes each, have shown that they have practically no effect on the transition to the state of meditation. The levels of the "meditation" parameter, and even just the two alpha rhythms (low and high) shown by the headset app, depended almost exclusively on the conscious transition to a state of meditation, and not on listening to binaural alpha beats in headphones. A trained mind can enter a state of meditation in a couple of seconds, which is incredibly more effective than any binaural beats. Perhaps they can help someone, but, in any case, this help is not the key one. You yourself will have to overcome anxiety and distraction of the mind. In this regard, it can be advised to everyone who hopes for a "magic wand" of various guided meditations with music and dictated affirmations, not to be in the illusion of allegedly being in meditation, and actually start meditating on their own. Meditation is a process controlled by your mind, not relaxation and nap to music and affirmations given in a pleasant voice.

Shamatha / samadhi meditation, if we talk about its real manifestation and effect, is a purely energetic thing. And this allows to formulate the correct approach to its practice.

While it is possible to train absence of thoughts to change mental patterns in the direction to meditation at any time and almost indefinitely, even an hour or longer (although the maximum periods of continuous absence of thoughts may still not exceed half a minute), meditation itself, or absence of thoughts-2.0, is impossible to hold longer than your current limit, just as it is impossible to continuously pull up for an hour if the current limit is only a dozen pull-ups. And if we continue this analogy further, then the actual limit of many novice meditators is comparable to the ability of a athlete-beginner to simply hang and twitch on the horizontal bar for 10 seconds until his hands become weak. Fortunately, science has made the ability to meditate clearly visible, whether someone likes it or not.

The use of the NeuroSky neuroheadset, the precise algorithm for determining the values of the "meditation" parameter of which was created as a result of many years of research of 14 meditation masters, including really experienced Tibetan Buddhist monks, shows that each meditator has a very specific limit of meditation. And no matter how much the meditator tries to continuously heave (strain) after reaching this limit, the success of such an attempt will be about the same as further attempts to pull up on the horizontal bar after reaching own physical limit.

An effective approach in this case would be to alternate short meditation workouts with breaks, as suggested by genuine masters of shamatha meditation, for example, Mingyur Rinpoche. Ten or more sessions of meditation a day for 1-2 minutes for a beginner and even an average meditator will be much more effective than one tortured continuous hour session a day, which does not bring an actual energetic result and generally discourages the urge to meditate. Moreover, such a tortured hour-long meditation session with the ability to meditate continuously for only a few tens of seconds (the personal limit of the duration of effective meditation of each meditator is easily checked by the NeuroSky neuroheadset) will lead to energy depletion, similar to physical overtraining in bodybuilding, when people pull iron for whole days, but their strength and muscles do not grow at the same time. The correct frequency and cyclicity of any training, including invisible meditation, are of paramount importance for achieving high results.

When using the NeuroSky neuroheadset, overtraining in meditation practice becomes easily noticeable. If you try to meditate for a long time on one day, then the next day it is almost impossible to give your average result with the headset, which has been regularly achieved over the past weeks. It will take 1-2 days until the necessary energy is restored, and only after that such a meditator can again demonstrate his usual results in meditation using scientific evidence of the effectiveness of shamatha / samadhi meditation.

From an interview with Chagdyr Sanjiev (2): "And in shamatha, it is best if you practice meditation in retreat. For example, in a long-term retreat. In this case, you will get the result (trained shamatha lasting 3-4 hours), according to different teachers, within from one and a half to three years. Some teachers say that highly developed people can reach shamatha in 6 months, but at the same time, if we do not deepen it, we can lose it within a week, for example, or two. It is necessary further to maintain it constantly". In other words, shamatha is not a talent (although a certain already achieved level of development of buddhi is necessary for its practice) and not even a skill, since such a skill cannot be lost so quickly.

Shamatha / samadhi meditation, when using the right technique, is an energetic buildup (or pumping or swing) that allows you to accumulate energy without any "secret energy meditation techniques" that various businessmen from spirituality like to write about in advertising slogans. Because the main secret of meditation is the correct shamatha technique, known in Buddhism for the last 2500 years.

How to meditate, or advice on meditation from the very beginning

1. First you should learn to concentrate. If someone is unable to focus mind on one object longer than, for example, ten seconds, then such person probably will not succeed in keeping the mind without thoughts for a long time. Not to mention those who are prevented from concentrating for a long time, for example, because of ADHD. On the Internet, there are many guides and techniques for training attention and concentration, for example, fixing a look at a candle flame or a point on a piece of paper.

2. If you are able to keep the mind on one object long enough, then you will be able to successfully train absence of thoughts. It is easy to train at any time, when there is no need to talk or think, and, of course, when you once again remember the need for this training. This can be done dozens of times during the day, and this is one of the most effective approaches to training the silence of the mind – the preparatory stage of meditation.

|

"My father always told all the new students, including me, that the most effective approach for a beginner is to calm the mind for a very short time many times a day." | |

– Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, “Buddha, Brain and Neurophysiology of Happiness. How to change lives for the better. Practical Guide” |

In addition, absence of thoughts has its own levels of subtlety, which also affect the level of meditation attained. Gradually you will begin to notice the moment of the appearance of thought and stop its manifestation in the mind at earlier stages of its emergence. Prolonged absence of thoughts in a state of wakefulness is the main prerequisite for successful meditation.

3. After you learn to keep the mind without thoughts, say, for 10 seconds, you can go to the practice of meditation itself. You need to take a stable position of the body, with which you do not need to strain any particular muscle group. The most optimal position of the body for meditation is not lying, when you quickly begin to experience drowsiness, not standing, when you will be too tense and active, but sitting. The back should be straight and vertical. The point here is not only in the ida, pingala and sushumna, but also that the straight vertical back is in optimal balance and requires the least physical effort to maintain its position and correct possible deviations. The minimum of physical activity is important for long-term successful meditation. The meditation posture should be comfortable. It makes no sense to sit in a lotus, if due to it in a few minutes you will begin to experience physical pain. Your meditation will only get worse because of such pain.

In addition, in order to achieve at least some noticeable yogic results in meditation practice, you will have to meditate for at least 3 hours a day every day for many years in a row. For example, this is how much meditation is practiced by those experienced Buddhist monks who practice meditation. If every day you sit for so much time with a crooked back, then, albeit slowly, but continuously renewed tissues and bones of the spine will form its curvature, and this is fraught with a wide variety of health problems in the future. If someone does not understand what meditation is and why it is necessary to practice it for so long, then he will not understand the importance of this requirement.

A quote from the article "Sankhya and Yoga" by the academician-neurosurgeon and translator of the Mahabharata from Sanskrit Boris Leonidovich Smirnov (1891-1967): "I think that some hints of texts remained outside the field of attention of specialists simply because, reading and understanding the text as philologists, they could not pay attention to its physiological significance. I am saying that with all exercises with breath holding, you should not create positive pressure, as well as stagnation of venous blood in the chest cavity and in its organs, in the abdomen (especially in the liver, spleen), in perineal plexus, as well as in the deposit formations of the spine and spinal cord. This is how the constant, emphasized requirement found in yogic texts is deciphered – when performing an asana, one must keep the head, neck, spine straight, on the same line".

At first it is recommended to meditate with closed eyes, as this reduces the distraction of the mind to external objects and its "noisiness". In addition, the activation of brain areas associated with the processing of visual information, activates the mind as a whole and can reduce the quality of meditation. In some schools of Buddhism it is recommended to meditate with half-closed eyes when you see only a small section of the floor in front of you. In this case, no new visual information appears, the activity of the brain and mind as a result is reduced, and not completely closed eyes prevent the sinking of the mind and drowsiness.

Also, for transition into a state of meditation it can be helpful to direct the "gaze" of the closed eyes slightly upward (when the mind is drowning) or down (when the mind is often distracted by thoughts), depending on the situation. In addition, it is necessary slightly to "defocus" the gaze (if this is basic shamatha, and not psychotechniques of Vajrayana visualizations), even if your eyes are closed, as this will also reduce the activity of the brain and noisyness of the mind. Not only thoughts, but also too coarse attention prevents one from entering the state of shamatha meditation. It is necessary to move from the gross "concrete" observation of the state of mind to the natural pure state of the uninvolved observer, in which there is no gross focusing of attention on any point or idea. The state of mind in shamatha meditation should be in the background, not involved in anything specific. The mind must be released (in the presence of a certain light alert state of the "observer"), it must be in its pristine primordial state, which is not tainted by any perceptions, expectations or intentions.

Such a state sometimes occurs on its own, for example, when a difficult problem is finally solved, or when a person, as a result of a long journey, has reached some quiet, bright, picturesque place (the edge of a forest, the bank of a deserted river, a halt in the mountains) and stopped to rest. It is difficult to describe in words this state of unearthed detachment of a clear, waking mind that does not slabber thought, but it is this state that actually corresponds to shamatha and is accompanied by the dominance of the alpha rhythm of the brain. To hold it "forcibly" for some lengthy time requires at least many months of training, as well as very calm and even breathing during meditation.

A fairly effective way to enter the state of meditation is to track your breath. This method is described in various ancient yoga texts, and its effectiveness, despite its apparent simplicity, is quite high. Thanks to breathing tracking, the mind, if it is not yet sufficiently trained in absence of thoughts and meditation, will be busy with this process, and the likelihood of its distraction by thoughts and semantic digestion of information is noticeably reduced.

With proper meditation, the level of "noisy" beta waves is reduced as a result of absence of thoughts of mind, and the level of alpha waves is increased as a result of absence of thoughts and maintaining the mind in a state of optimal balance between states of increased activity and fatigue / drowsiness (mind sinking).

One of the key points of the dominant alpha waves – you should not even try to come up with a further topic for your thoughts. It is necessary to maintain such a fixed and steady clear mind as possible.

It is said in the scriptures that the diet of meditator should be moderate. Experiments with the NeuroSky headset also show that stable high values of the "Meditation" parameter can appear only since 3 hours after consuming a large single amount of food.

Gradual progress in meditation is possible only as a result of a long and proper practice. It may take years to keep the mind without thoughts for a minute or longer. External factors of society even can make it impossible to make significant progress in meditation.

|

"NeuroSky, Muse, Meditation" group on Facebook |

One of the hardest things about learning or teaching meditation is that there is no single, explicit direct effort that would lead to being in a state of true meditation for more than a couple of seconds.

In many ways, it is this discouraging uncertainty and uncontrollability of the state of meditation, which requires the training of "indirect" efforts, that determines the worldwide expansion of postural yoga fitness, in which, as opposed to meditation, it is quite possible to apply direct efforts to affect the joints and ligaments to ensure the progress given in physical sensations.

Meditation is freeing the mind from any effort. It is a basic state of a clear, clean, and non-thoughtful mind that does not label what is happening, does not sink into memories, and does not generate expectations and anxiety about the future. It sounds corny, but it is exactly so. A more confident understanding of this idea comes only with the practice of meditation.

The study of meditation is different from anything the mind has studied before. If in other cases concentrated efforts are needed, then in meditation it is required to achieve its state through letting go of efforts, leaving minimal control, the degree of which decreases and becomes more refined with each subsequent jhana. Untrained consciousness can appear in a state of meditation only spontaneously and for a short time.

Meditation is purely a skill, but the study of meditation is methodologically different from anything the mind has studied before.

Summarizing, we can say that meditation is a state of absence of thoughts of a clear mind-observer who is not inclined to fall asleep and is not too excited. The further practice of meditation will allow you to gradually move on to new, more subtle levels of meditation and awareness. These levels are described in detail in Buddhism (for example, different kinds of samadhi).

An excellent opportunity to track the stay in a state of meditation that has become available only in recent years is the use of the relatively inexpensive (about $100) NeuroSky MindWave EEG headset. Even before the development of its first version of the EEG headset, NeuroSky conducted long-term studies with the help of professional multi-channel electroencephalographs of meditative states of 14 different meditation masters, including Tibetan monks with large retreat experience. It is on the basis of these studies that a proprietary algorithm for calculating the "meditation" parameter was developed. The studies were similar to those described in this article.

|

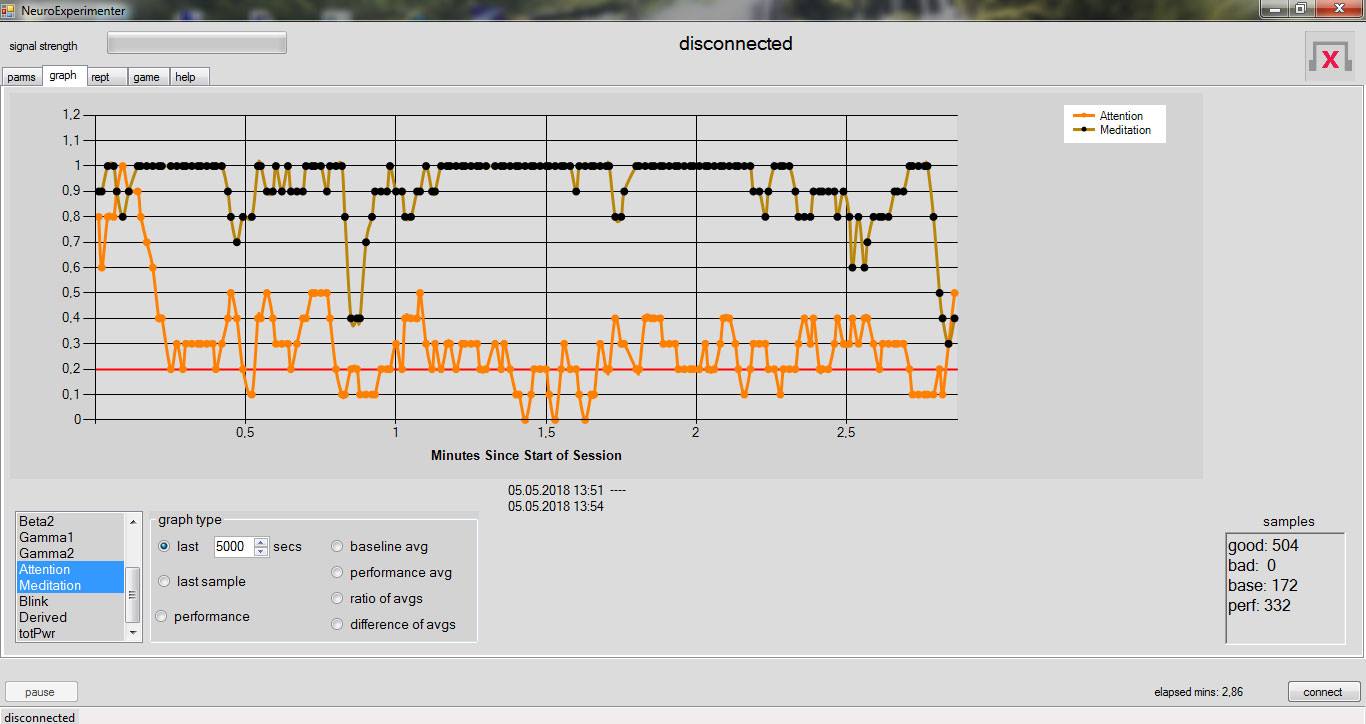

An example of a screenshot of the application NeuroExperimenter for the NeuroSky MindWave EEG headset. |

It should be noted that the use of the NeuroSky headset will not help in the study of meditation if a person is unable to keep the mind without thoughts, say, for 10 seconds. The values of the "meditation" parameter will chaotically jump, and it will be unclear how these values can be controlled at all. And the progress in meditation is very slow, and this can quickly lead to disappointment. In such a situation, one should practice the preliminary condition of meditation – absence of thoughts, and this is possible without any EEG headset. At the same time, an important feature of the NeuroSky EEG headset is that even with your prolonged absence of thoughts, it will show whether you are at this moment in a state of meditation that is not achieved only by absence of thoughts.

Success in meditation requires daily practice, practice and practice once again.

The quality of shamatha meditation is determined by how much the practitioner is able to notice the appearance of subtle distractions, intentions and small twitchings (disturbances) of the mind, and, accordingly, how much a person is able to prevent them from manifesting. Many have heard this phrase in one variation or another before. This is the essence of chitta-vritti-nirodha (yoga), as well as that absolute peace of a clear mind that meditators talk about, and which must be maintained in meditation through subtle intention.

|

If one confirms the presence of a state of meditation scientifically through the NeuroSky neuroheadset, then the difference becomes noticeable between those who actually meditate and those who, after reading something about meditation, while sitting on the rug, wasting their time to no avail, doing whatever, but just not meditation.

Moreover, such a person may even have the absence of explicit (coarse) thoughts, but the presence of constant subtle distractions, intentions and small twitchings of the mind, which are simply not tracked and are not even realized at this stage of practice, will still not allow one to enter a state of meditation and achieve its characteristic effects, for example, slowing down breathing in prolonged meditation (from several minutes). In addition, in just a couple of seconds the presence of meditation is shown by the NeuroSky neuroheadset, which reacts incredibly correct to any distractions, intentions and even small twitching of the mind.

The practitioner's unawareness of these at first almost imperceptible disturbances of the mind can force one to draw conclusions that the neuroheadset allegedly "shows something wrong", that practitioner allegedly knows how to meditate, etc. But the harsh truth is that one must learn to meditate in a proper way, and that to maintain this skill one must train every day with the necessary minimum of effort. Moreover, as the practice progresses, this minimum rises.

Yes, this neuroheadset, unlike a guru or a book, will not at first explain to you how to meditate correctly. But it impartially every second (with a technical delay of 1-2 seconds) displays the level of your meditation at the moment and tells you whether this state is meditation at all.

Get rid of superstitions and prejudices in your meditation practice – both borrowed from books "about meditation" by those authors who did not meditate or even did not know how to meditate, and your own simplified and superficial understandings and representations of statements about meditation from the books of Swami Sivananda and other yoga realized personalities who are not always understandable due to the semantic scarcity of languages, especially Western ones, when describing something that has never been encountered large enough in society in order to form the necessary well-known lexemes in the language.

P. S.

1. If you meditate less than a couple of times a day for at least 15 minutes a day, then there will be no progress in meditation as such. If you want to progress in realistically confirmed indicators – meditate more often, maybe even in shorter sessions. 20 meditation sessions a day, 2 minutes each, will bring both a beginner and even an average meditator more benefits than 2 sessions of 20 minutes a day. Because out of those 20 minutes of sitting in meditation, meditation itself will still last, as statistics show, a maximum of 1-2 minutes, and these minutes of meditation will usually be closer to the beginning of the session.

2. If, according to objective data, for example, of neuroheadset, you can already meditate for a couple of minutes with an average meditation level of at least 80%, or keep the meditation level for more than a minute without falling below 80%, then for further progress you will have to increase meditation sessions for example, up to 20 minutes or more. The number of sessions can be 4 or slightly more per day.

3. If you do not practice meditation for 3-4 days, then the objective indicators of meditation usually deteriorate 2-4 times. If you do not practice meditation for a week, then the objective indicators of meditation usually deteriorate by 5-10 times. When you resume the practice of meditation, it will take several (3-4) days to return the indicators partially, and about a couple of weeks of regular practice to return them to almost the initial level before the break.

Based on this, I can say that those who meditate only 2-3 times a week will actually not make progress in the practice of meditation. At best, they will flounder around their basic (minimum) meditation level. These are the objective data supported by NeuroSky neuroheadset with "meditation" parameter.

P. P. S. Brief description of self-realization

Self-realization is yoga realization achieved by building anandamaya-kosha from the subtlest energy, which manifests itself with an incredible increase in the flow of kundalini in kevala-kumbhaka during the regular three-hour practice of shamatha, which is achieved by repeated daily practice of meditation.

Another very important point is the sincere practice of metta, or loving-kindness and compassion. On the one hand, this, along with vipashyana, contributes to the elimination of the feeling of "doer" and, as a result, to the reverse outflow of karma to its real sources, which removes obstacles in the practice of meditation by clearing away any karma. On the other hand, we are all 24 hours a day beheld by much more developed beings from space with a greater dimension than our three-dimensional. All thoughts, words and deeds of every creature here, along with motivation, are quite obvious to them. Almost everything that happens here is somehow conditioned or furnished from there by their opinions. The sincere practice of metta improves their opinion of us and, accordingly, our destiny, giving the green light to the whole practice of self-realization.

This text was written after studying many scriptures of yoga and Buddhism, among which were "Yoga Rahasya" by Dattatreya, "Yoga Kundalini Upanishad", "Shandilya Upanishad", "Tripura Rahasya", "Buddhist meditation" by Samdhong Rinpoche, and others, and also as a result of many years of living in Indian monasteries and ashrams.

More details:

The stages of self-realization, starting with the mundane, ultimately lead to the path of yoga realization as a result of the gradual formation of subtle body-shells (up to anandamaya-kosha) in the process of development of consciousness, with a corresponding expansion of the horizons of vision and a natural successive change in the level of interests to less and less material values.

Anandamaya-kosha is built as the last of the koshas, and its formation requires the greatest amount of the most subtle kundalini energy.

The flow of kundalini is incredibly amplified naturally during kevala-kumbhaka – prolonged natural holding of the breath, and not during the "secret Tibetan or American Indian practices" and "ancient" teachings that appeared not earlier than in 20th century. Raising the kundalini through visualization is about as effective as levitating the body as a result of visualization, since both the raising of the kundalini and the levitation result from kevala kumbhaka, not visualizations.

Long-term natural retention of breath is achieved in shamatha meditation. Other methods of attaining kevala kumbhaka actually copy the techniques of meditation. The duration of shamatha – continuous meditation without a single thought – is 3 hours or longer.

Shamatha is achieved by daily meditation practice, several sessions a day, at least 4 sessions of 10-20 minutes each, or 20 sessions of at least 2 minutes each day. Read more about shamatha here.

Many people, hearing the word vipassana, are confused about the understanding of this term, which has become very ambiguous.

Vipassana (vipassanā in the Pali language) or vipashyana (vipaśyanā in Sanskrit) literally means "penetrating vision" or "insight" and is a Buddhist psychotechnique that should be applied after mastering shamatha (continuous meditation for 3-4 hours). In Western languages, vipassana is usually called meditation along with shamatha, although in Eastern languages all psychotechniques have their own separate names (vipassana is precisely vipassana, and not an abstract meditation).

Like the terms “yoga” and “meditation”, the meaning of vipassana has also changed and expanded over time, gaining several new interpretations as a result of the emergence of new directions of practices, created by various charismatic personalities, mainly Buddhist monks of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The original essence of vipassana in the Buddha's teachings is an almost instantaneous insight into the essence of things (for example, the four noble truths and the idea of impermanence) at the level of clairvoyance thanks to the new super-powerful cognitive tools (buddhi and sambhogakaya) that appeared as a result of attaining 3-hour shamatha. With the help of these new tools, consciousness has an incredible power of focusing on any object or idea, it becomes possible to quickly and accurately become aware (usually recursive) of any object or idea. Vipassana is considered a "dynamic" analytical psychotechnique, as opposed to "static" shamatha.

In the West, vipassana is best known as a 10-day group retreat according to the Goenka method (a disciple of Sayagyi U Ba Khin). Sri Satya Narayan Goenka began teaching vipassana in 1969. Many of those who attended Goenka's vipassana courses consider this as one of the best things in their lives. Such courses are the most concentrated practice of spirituality.

The original vipassana (vipashyana):

During the eighth talk, "Meditation in the Dzogchen Tradition", held on May 6, 2021, Sangnak Tenzin Rinpoche gave a very important and rare description of what exactly is implied under analytical meditation and vipashyana (and these are still different things) in the Dzogchen tradition of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism. In fact, this description is also suitable for other schools of Tibetan Buddhism, since shamatha and vipashyana are not something unique and characteristic of the Nyingma school alone. Moreover, the psychotechnics shamatha and vipashyana do not have any fundamental differences in different schools of Buddhism, since their descriptions are ultimately rooted in the Theravada teachings (Pali canon).

The essence of Sangnak Tenzin Rinpoche's description boils down to the fact that what Buddhists call analytical meditation is not the Vipashyana (instant "insight" into the essence of things) that Buddhism speaks of. And therefore, such analytical meditation can indeed be practiced without attaining 4 contiguous hours of shamatha. But the fruits of such analytical meditation will not be instant insights into the essence of things at the level of clairvoyance, but just ordinary logical conclusions and inferences obtained with varying degrees of accuracy and reliability. Also about the impossibility of practicing vipashyana without first attaining shamatha see here the words of XIII Kundeling Rinpoche. It should be noted that the Sanskrit word vipashyana has been translated into Tibetan as "lhagtong" ("divine, or supreme, vision"), and therefore such an ability cannot be expected from an ordinary untrained mind without attaining 4 contiguous hours of shamatha.

A separate problem is that many Buddhists, due to this confusion of concepts, confuse such analytical meditation with vipashyana and, as a result, claim that vipashyana allegedly can be practiced in parallel with the practice of shamatha even before reaching its 4-hour duration. But such "analytical meditation" was not even close to real vipashyana in its effectiveness. Such "analytical meditation" (along with any other purposeful thinking) is only capable of developing mind-manas (the third body in the structure of pancha-kosha – five bodies – of Hinduism; developed by logic, by debates, etc.), and therefore cannot bring prajna (supreme wisdom), for the acquisition of which it is required to fully develop vijnanamaya kosha (buddhi; fourth body; it is developed by regular meditations, even if relatively short) and to a large extent anandamaya kosha (fifth; it is developed by regular meditations for 4 contiguous hours and longer, that is, achieved by shamatha).

It should also be noted that in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali there is no description of a separate learning of any analogue of vipashyana. The analogue of vipashyana in Yoga Sutras of Patanjali is samyamas, which are performed after training samadhi (the 8th part of the eight-part yoga of Patanjali; yogic samadhi is an analogue of shamatha in Buddhism). In Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, samyamas are simply performed on certain objects and phenomena thanks to the new super-powerful cognitive abilities that have appeared as a result of trained samadhi. Similarly, vipashyana as a separate category (or separate psychotechnique) is absent in Chinese Chan Buddhism, as well as in the most popular Soto (Soto-shu) school of Japanese Zen Buddhism, in which the main psychotechnique is zazen – an analogue of shamatha with its dhyanas. Perhaps this is due to the fact that, like in Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the key point of yoga realization is precisely the training of 4 contiguous hours of shamatha, and the subsequent results of vipashyana – the acquisition of prajna (supra-mundane wisdom) – are achieved in any case, even with ordinary daily activities thanks to the new super-powerful super-insightful cognitive abilities and a comprehensive in-depth study of any occurring phenomenon, while mind-manas without trained shamatha may lack cognitive abilities ("computing power") and time even for a simple analysis of the next situation.

Sangnak Tenzin Rinpoche's quote from video 1:24:07-1:25:20 (you can choose English translation of subtitles):

"And at the end you ask the question: “Thinking and meditating in this way, can you understand all this?” Of course, simple thinking – analytical meditation – helps us to understand the ultimate nature of reality through a gross mental image, but if we are talking about meditative absorption, then in this state we no longer need analytical meditation, we do not need a thought process. We directly comprehend the way in which all phenomena are realized. However, as I said above, analytical meditation – thinking – is beneficial because it helps us between sessions (of shamatha), in the intervals between (shamatha) meditation sessions to hone our skills, hone our knowledge and skills (that is, develop at least mind-manas, in while shamatha develops buddhi)".

Also one more quote from here:

“It should be noted that for a long time there has been a debate between Buddhist teachers about whether the practice of vipassana (vipashyana) can lead to supramundane wisdom without proper development of concentration (jhanas; 8-9 dhyanas in shamatha). Those who believe that this is possible base their point of view on the canonical commentaries. Opponents of this statement note that in the Pali canon itself this idea is very weakly expressed, but very often the emphasis is placed on the development of jhana (shamatha) to achieve supra-mundane wisdom (prajna, achieved in vipashyana on the basis of the already achieved 4-hour shamatha). In MN 64, the Buddha denies that it is possible to destroy five (and, logically, all ten) samsaric fetters without jhana. "

MN 64 is the Mahamalunkya Sutta, the 64th text of the Majjhima Nikaya collection. This collection is the second of five nikayas in the Sutta Pitaka, the second of the three parts of the Tripitaka (Tipitaka in Pali), also known as the Pali Canon. The Theravada teachings, which are part of the Mahayana Buddhist teachings, are based on the texts of the Pali canon.

Below is one of the modern views on how shamatha relates to vipashyana in Theravada:

"According to Thanissaro Bhikkhu, in the sutta pitaka the term "vipassana" is hardly mentioned, while they frequently mention jhana (dhyana, an element of shamatha) as the meditative practice to be undertaken. When vipassana is mentioned, it is always in tandem with samatha, as a pair of qualities of mind which are developed. According to Thanissaro Bhikkhu, "samatha, jhana, and vipassana were all part of a single path". Norman notes that "the Buddha's way to release [...] was by means of meditative practices (i.e. primarily by dhyana)". According to Vetter and Bronkhorst, dhyana constituted the original "liberating practice". Vetter further argues that the eightfold path constitutes a body of practices which prepare one, and lead up to, the practice of dhyana. Vetter and Bronkhorst further note that dhyana is not limited to single-pointed concentration, which seems to be described in the first jhana, but develops into equanimity and mindfulness, "born from samadhi" but no longer absorbed in concentration, being mindfully aware of objects while being indifferent to it, "directing states of meditative absorption towards the mindful awareness of objects"."

As a conclusion, we can point out that after many thousands of years of piling up new meanings and interpretations over and around the word "vipashyana", most likely, it will never be possible to find out its original meaning. It is even less likely that the original meaning of this term, even if it is clarified, will become generally accepted. A similar story also happened with other important terms related to spiritual practices of self-development – "chitta", "buddhi", "samadhi", "dhyana" and even "yoga", etc., while the correct understanding of these terms is of fundamental importance for the correct implementation of meditative practices of yoga and Buddhism. The existence of different versions about the origin and meaning of these words allows philologists, philosophers and preachers to spread different versions, but none of them allows one to move from the purportless stage of serial meditative tautology to the phase of unconditional uniqueness and exclusive authenticity.

Vipassana in the modern understanding of the Pali canon:

In the suttas (in Sanskrit – sutras; sayings) of the Pali canon, the Buddha and his disciples use the phrase "vipassana-bhavana", which means "development (bhavana) of vision-as-is (vipassana)". Those engaged in such development must come to the realization of impermanence (impermanence, anicca or anichcha in Pali; anitya in Sanskrit), unsatisfactoriness (or suffering, dukkha; duhkha in Sanskrit) and impersonality (anatta; anatman in Sanskrit) of the phenomena of experience (dhamma; dharma in Sanskrit). Such a practice should lead to disidentification with the elements of experience and, thus, eliminate the precondition for the appearance of psychological and then physical suffering.

In the suttas, the Buddha offers several approaches to the practice of vipassana. In the Pali canon, vipassana-bhavana is the second of the two main elements of practice, along with shamatha-bhavana – the development of calmness, composure and subtle concentration, that is, the training of meditation.

Vipashyana in Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhism:

The Sanskrit word vipashyana has been translated into Tibetan as lhagtong (divine or supreme vision). Different traditions of Tibetan Buddhism teach different vipashyana techniques; as a rule, the psychotechnique of vipashyana in Tibetan Buddhism is aimed at recognizing the emptiness of the mind and the world.

Vipassana in modern Theravada (Southern Buddhism):

In the 19th century in Myanmar (Burma), Buddhist monks developed a number of psychotechniques based on the Pali canon, which became known as vipassana.

At the moment, "vipassana" is most often called the techniques taught by Mahasi Sayadaw and, especially in the West, by Satya Narayan Goenka. In India and other countries, especially in the West, the 10-days Goenka’s vipassana courses have become very popular, while in traditionally Buddhist countries – Thailand, Myanmar and Sri Lanka – you can often find vipassana according to Mahasi Sayadaw (the basic course lasts 14 days, sometimes longer). In the countries of Western Europe and North America, there are various traditions in which vipassana is taught. In the Goenka tradition, they distance themselves from religiosity in general, including Buddhism, while other teachers see vipassana as part of the Buddhist tradition. Both the Goenka courses and the vipassana training in the Buddhist tradition are generally free.

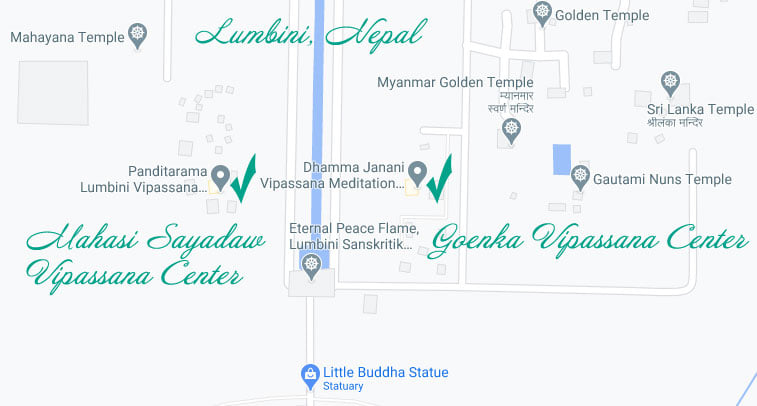

At the birthplace of Buddha – the village of Lumbini in Nepal – the centers of vipassana of Goenka and Mahasi Sayadaw are located 200 meters (in a straight line, 500 meters along the road) from each other, see screenshot.

The centers of vipassana of Goenka and Mahasi Sayadaw in Lumbini, Nepal. |

Vipassana of Goenka:

At vipassana of Satya Narayana Goenka (1924-2013), courses begin by observing natural (i.e. uncontrolled) breathing, which allows the mind to concentrate. This practice is called anapana (anapanasati, anapanasati). It prepares for the practice of vipassana itself, which in this tradition includes observing all types of bodily sensations, developing awareness and balance in relation to them, and a gradual awareness of the relationship between mind and body. During the courses, you cannot talk, eat food brought with you (and only vegetarian meals are available on the courses), and you should strictly follow the ascetic schedule.

Vipassana of Mahasi Sayadaw:

In vipassana of Mahasi Sayadaw (1904-1982), the practitioner must learn to concentrate on "uterine breathing" – the movements of the abdomen during inhalation and exhalation, as well as other sensations and thoughts. The duration of the basic course is 14 (sometimes longer) days, and a 10-day retreat for those who have already completed the basic course.

The full version of the technique offers many other exercises, including the development of mindfulness when walking. For example, an hour of breath-tracking practice is alternated by a participant of satipatthana-vipassana course with an hour of slow, mindful walking. With each step, you need to focus more and more on the movement of the leg, on how the foot moves from the moment of raising to the moment of its lowering.

One of the mistakes of vipassana of Mahasi Sayadaw is the method of verbal reporting on the presence of a bodily and psycho-emotional state that violates the state of meditation. Perhaps this is acceptable for beginners who anyway do not know how to meditate for more than a couple of seconds, but, nevertheless, this is a methodological mistake.

The second feature, which some consider to be a disadvantage, is the use of the method of contemplation of breath (anapanasati) instead of full control of breathing (pranayama) as a preparatory practice for full satipatthana.

Summing up the above about vipashyana, it should be noted that in early Buddhism, when describing the eighth stage of the noble eightfold path – samyak samādhi, or "correct concentration", which means the psychotechnics of shamatha, vipashyana was not yet a separate psychotechnique. It was just an aspect of the use of full-fledged shamatha, without which vipashyana, as follows from the Pali canon, was impossible in practice. Formation of vipashyana as a separate psychotechnique and a kind of meditation occurred only in the 4th-5th centuries as a result of the activities of the Mahayana Buddhist thinker Asanga (4th century) and Theravada Buddhist thinker Buddhaghosha (5th century, author of the “Visuddhimagga” treatise).

The teachings of Asanga and especially Buddhaghosha contained relatively vague descriptions of vipashyana, which allowed various interpretations of its essence. This was especially true of those interpreters who did not have their own experience of 3-hour shamatha and full-fledged vipashyana. Subsequently, some Buddhist thinkers began to argue that the practice of vipashyana is possible in parallel with the practice of shamatha, which is true after reaching the 3-hour shamatha, but meaningless before such attainment. Some theorists and translators of Buddhism in recent centuries, especially in the Mahayana tradition, due to the confusion and simplification of concepts (parallel > simultaneously; vipashyana > analytical meditation > reasoning & thinking), went even further and, as a result, even began to declare the use of thoughts in the first jhana / dhyana. For example, V. P. Androsov in his monograph “Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. The Encyclopedic Dictionary” on page 44 writes: “The Buddhist first dhyana is the practice of being in joy and pleasure, accompanied by thinking, the study of causes and thoughts”. It should be noted here that the point of view of Theravada Buddhists on the requirements and properties of the first jhana / dhyana is fundamentally different – it is considered an extremely difficult to achieve state of complete peace of a silent clear mind, which, moreover, can be accompanied by even nimitta (seeing a bright light with closed eyes). It should not be forgotten that both Theravada and Mahayana representatives position themselves as the authoritative carriers of the original teachings of the Buddha.

Also, one should not forget that the first dhyana (and all subsequent ones) refers to shamatha, in which thoughts are clearly one of two obstacles along with drowning (pre-drowsy state) of the mind.

This is a translation into English of this article of the author of this site, 2018.

Meditation with biofeedback using the electroencephalograph gadget NeuroSky MindWave Mobile, or accelerated self-study of meditation.

The free 'EEG Meditation' app for Android.

The free 'EEG Meditation' app for Windows PC, for the white or black headsets.

The arguments in favor of the use of EEG headsets, such as NeuroSky MindWave Mobile, for meditation.